Session-based Recommenders

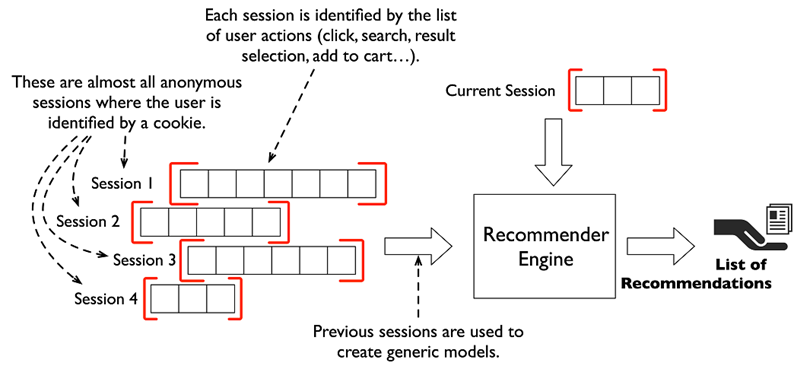

Recommender systems help users find relevant items of interest, for example on e-commerce or media streaming sites. Most academic research is concerned with approaches that personalize the recommendations according to long-term user profiles. In many real-world applications, however, such long-term profiles often do not exist and recommendations, therefore, have to be made solely based on the observed behavior of a user during an ongoing session.

Session-based recommendations

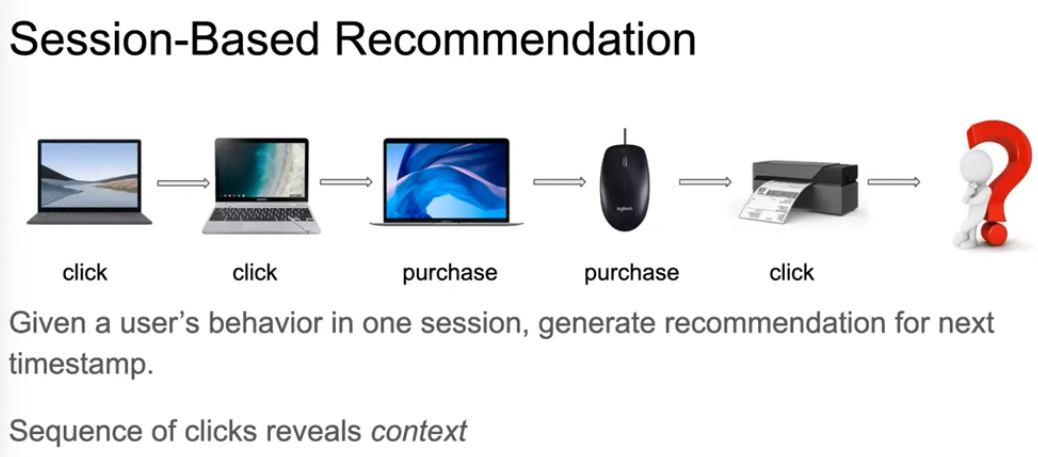

Session-based recommendation is an important task for domains such as e-commerce, news, streaming video and music services, where users might be untraceable, their histories can be short, and users can have rapidly changing tastes. Providing recommendations based purely on the interactions that happen in the current session.

Given the high practical relevance of the problem, and increased interest in this problem can be observed in recent years, leading to a number of proposals for session-based recommendation algorithms that typically aim to predict the user’s immediate next actions. Recommendation techniques that rely solely on the user’s actions in an ongoing session and which adapt their recommendations to the user’s actions are called session-based recommendation approaches [Quadrana et al. 2018]. Amazon’s “Customers who bought . . . also bought” recommendations can be considered an extreme case of such a session-based approach. In this case, the recommendations are seemingly only dependent on the item that is currently viewed by the user (and the purchasing patterns of the community).

Introduction

Session-based recommendation tasks are performed based on the user's anonymous historical behavior sequence and implicit feedback data, such as clicks, browsing, purchasing, etc., rather than rating or comment data. The primary aim is to predict the next behavior based on a sequence of the historical sequence of the session. Session-based recommendation aims to predict which item a user will click next, solely based on the user’s current sequential session data without access to the long-term preference profile.

The input to these systems are time-ordered logs of recorded user interactions, where the interactions are grouped into sessions. Such a session could, for example, correspond to a listening session on a music service, or a shopping session on an e-commerce site. One particularity of such approaches is that users are anonymous, which is a common problem on websites that deal with first-time users or users that are not logged in. The prediction task in this setting is to predict the next user action, given only the interactions of the ongoing session. Today, session-based recommendation is a highly active research area due to its practical relevance.

Markov chains is a classic case, which assumes that the next action is based on the previous ones. Many sequential recommendation methods based on the Markov chain (MC) model predict the next item based on the previous one through computing transition probabilities between two consecutive items. FPMC models the sequence behavior between every two adjacent clicks and provides a more accurate prediction for each sequence by factoring the user's personalized probability transfer matrix. The main problem with Markov methods, however, is that they assume too strongly the independence of more than two consecutive actions, so a great number of important sequential information cannot be well exploited for sessions with more than two actions.

The proposal of recurrent neural network (RNN) has obtained promising results in the session-based recommendation system, which has been proved to be effective in capturing users' preference from a sequence of historical actions. GRU4REC achieved significant progress over conventional methods. Because of their excellent performance, many followers began to try this method. Tan et al. further propose two techniques to improve the performance of session-based recommendation. Although these methods have improved the performance of session-based recommendation, they are all restricted by the constraints of RNNs that both the offline training and the online prediction process are time-consuming, due to its recursive nature which is hard to be parallelized. RNN-based methods hold that there is a strict sequential relationship between two adjacent items in a session, which restricts the extraction of the characteristics of session dynamic changes.

After the successful application of Transformer in Natural Language Processing (NLP), many attention-based models have been designed, which has been shown that comparable performance with RNNs in many sequence processing tasks. Li et al. proposed a hybrid RNN-based encoder with an attention layer, which is called neural attentive recommendation machine (NARM), employs the attention mechanism on RNN to capture users’ features of sequential behavior and main purposes. NARM is designed to capture the user’s sequential pattern and main purpose simultaneously by employing a global and local RNN. Then, a short-term attention priority model (STAMP) using simple MLP networks and an attentive net, is proposed to efficiently capture both users’ general interest and current interest. However, it only takes the future mean value of all items in the session as the context, without taking the dynamic variations and local dependencies of the sequence into account. A position-aware context attention (PACA) model for session-based recommendation has was proposed in 2019, which takes into account both the context information and the position information of items. However, this method only trains an additional implicit vector for each item and has little performance improvement for session-based recommendation tasks.

Xu et al. proposed Graph Contextualized Self Attention Network for Session-based Recommendation, which is a combination of GNN and attention mechanisms, and further improves the accuracy of the recommendation.

A session is a chunk of interactions that take place within a given time frame. It may span a single day, or several days, weeks, or even months. A session usually has a time-limited goal, such as finding a restaurant for dinner tonight, listening to music of a certain style or mood, or looking for a location for one’s next holiday.

Session data has many important characteristics:

- Session clicks and navigation are sequential by nature. The order of clicks as well as the navigational path may contain information about user intent.

- Viewed items often have metadata such as names, categories, and descriptions, which provides information about the user’s tastes and what they are looking for.

- Sessions are limited in time and scope. A session has a specific goal and generally ends once that goal is accomplished: rent a hotel for a business trip, find a restaurant for a romantic date, and so on. This means that the session has intrinsic informational power related to a specific item (such as the hotel or restaurant that’s eventually booked).

What SRS's are important?

- Caveats of user identification technologies

- Cookies and browser fingerprinting can not always recognize users correctly, especially across different devices and platforms

- Opt-out users are not tracked across sessions

- Privacy concerns for opt-in users

- Infrequent user visits, cookie expiration - Users visiting a site infrequently can not be recognized over long time

- Changing user intent across sessions - On many domains, users have session-based traits (short video sites, marketplaces, classified sites, etc.)

- Earlier solutions for handling sessions was only based on last user click and ignored user interactions in the session

Tasks

- Predict the next item (evaluated by ranking metrics like MRR)

- Predict all subsequent items in the current session (evaluated by metrics like precision, F1)

Methods

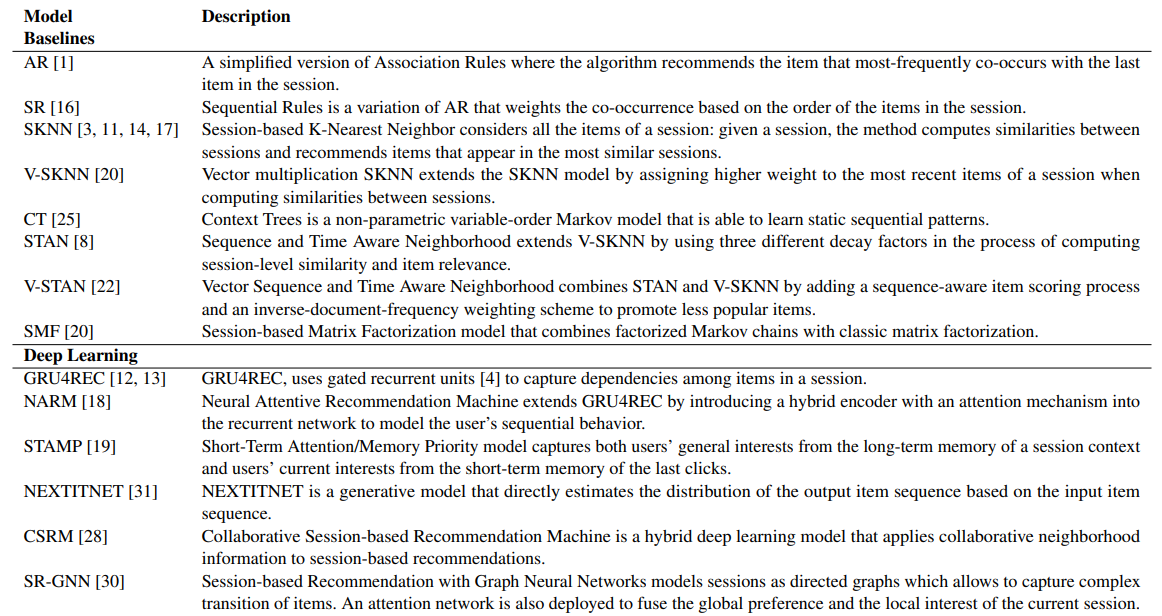

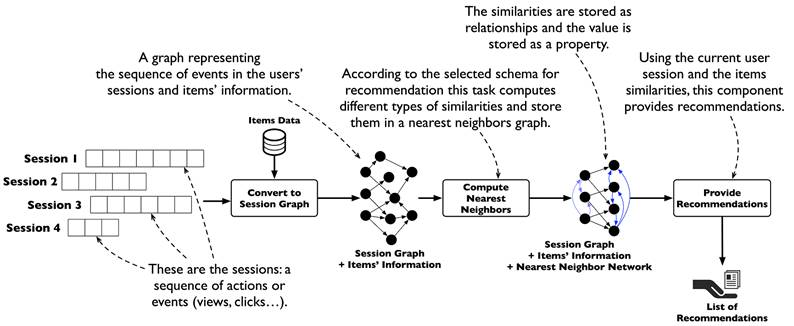

](/recohut/assets/images/content-concepts-raw-session-based-recommenders-untitled-4-3061abc4ed2a476171edf6b0dfa03e40.png)

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2010.12540.pdf

Simple Association Rules (ar)

Simple Association Rules (ar) are a simplified version of the association rule mining technique [Agrawal et al. 1993] with a maximum rule size of two. The method is designed to capture the frequency of two co-occurring events, e.g., “Customers who bought . . . also bought”. Algorithmically, the rules and their corresponding importance are “learned” by counting how often the items i and j occurred together in a session of any user.

Markov Chains (mc)

The mc baseline can be seen as a variant of ar with a focus on sequences in the data. Here, the rules are extracted from a first-order Markov Chain, which describes the transition probability between two subsequent events in a session. It can simply be a count of how often users viewed item q immediately after viewing item p.

Sequential Rules (sr)

Sequential Rule is a variation of mc or ar. It takes the order of actions into account, but in a less restrictive manner. In contrast to the mc method, we create a rule when an item q appeared after an item p in a session even when other events happened between p and q. When assigning weights to the rules, we consider the number of elements appearing between p and q in the session. Specifically, we use the weight function wsr(x) = 1/(x), where x corresponds to the number of steps between the two items.

Item-based kNN (iknn)

The iknn method only considers the last element in a given session and then returns those items as recommendations that are most similar to it in terms of their co-occurrence in other sessions. Technically, each item is encoded as a binary vector, where each element corresponds to a session and is set to “1” in case the item appeared in the session. The similarity of two items can then be determined, e.g., using the cosine similarity measure, and the number of neighbors k is implicitly defined by the desired recommendation list length.

Session-based kNN (sknn)

Instead of considering only the last event in the current session, the sknn method compares the entire current session with the past sessions in the training data to determine the items to be recommended. Technically, given a session s, we first determine the k most similar past sessions (neighbors) Ns by applying a suitable session similarity measure, e.g., the Jaccard index or cosine similarity on binary vectors over the item space.

Vector Multiplication Session-Based kNN (v-sknn)

iknn and sknn do not consider the order of the elements in a session when using the Jaccard index or cosine similarity as a distance measure. The idea of this variant is to put more emphasis on the more recent events of a session when computing the similarities. Instead of encoding a session as a binary vector as described above, we use real-valued vectors to encode the current session. Only the very last element of the session obtains a value of “1”; the weights of the other elements are determined using a linear decay function that depends on the position of the element within the session, where elements appearing earlier in the session obtain a lower weight. As a result, when using the dot product as a similarity function between the current weight-encoded session and a binary-encoded past session, more emphasis is given to elements that appear later in the sessions.

Sequential Session-based kNN (s-sknn)

This variant also puts more weight on elements that appear later in the session. This time, however, we achieve the effect with a different scoring function. The indicator function is complemented with a weighting function , which takes the order of the events in the current session s into account. The weight increases when the more recent items of the current session s also appeared in a neighboring session n.

Sequential Filter Session-based kNN (sf-sknn)

This method also uses a modified scoring function but in a more restrictive way. The basic idea is that given the last event (and related item ) of the current session s, we only consider items for the recommendation that appeared directly after in the training data at least once.

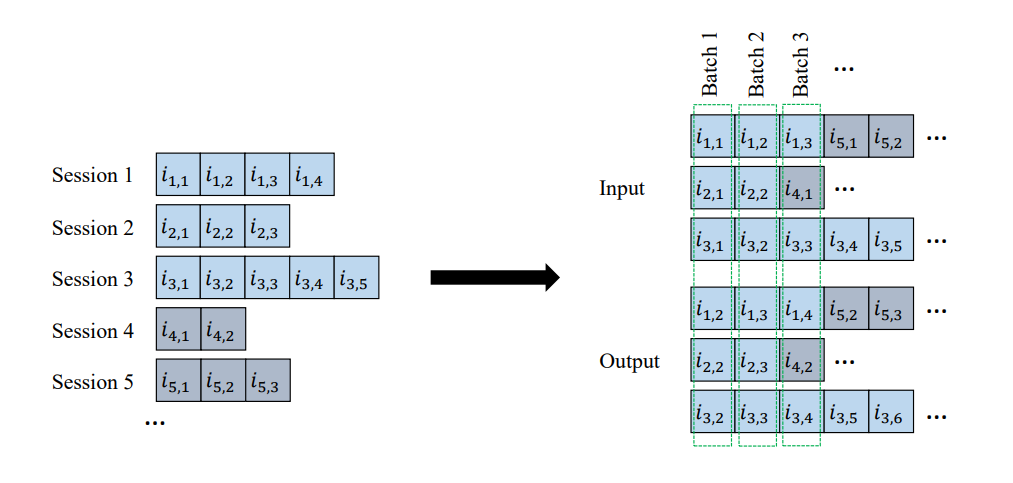

GRU4REC

gru4rec models user sessions with the help of an RNN with Gated Recurrent Units [Cho et al. 2014] in order to predict the probability of the subsequent events (e.g., item clicks) given a session beginning. The input of the network is formed by a single item, which is one-hot encoded in a vector representing the entire item space, and the output is a vector of similar shape that should give a ranking distribution for the subsequent item.

session-parallel mini-batch scheme for training

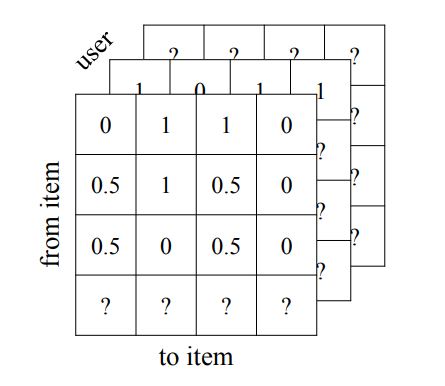

Factorized Personalized Markov Chains (fpmc)

The fpmc method was designed for the specific problem of next-basket recommendation. The problem consists of predicting the contents of the next basket of a user, given his or her history of past shopping baskets. By limiting the basket size to one item and by considering the current session as the history of baskets, the method can be directly applied for session-based recommendation problems. Technically, fpmc combines mc and traditional user-item matrix factorization in a three-dimensional tensor factorization approach. The third dimension captures the transition probabilities from one item to another.

Internally, a special form of the Canonical Tensor Decomposition is used to factor the cube into latent matrices, which can then be used to predict a ranking. In our problem setting, where we have no long-term user histories, each session in the training data corresponds to a user. Once the model is trained, each new session therefore represents a user cold-start situation. To apply the model to our setting, we estimate the session latent vectors as the average of the latent factors of the individual items in the session.

Use Cases

This problem is well-aligned with emerging real-world use cases, in which modeling short-term preferences is highly desirable. Consider the following examples in music, rental, and product spaces.

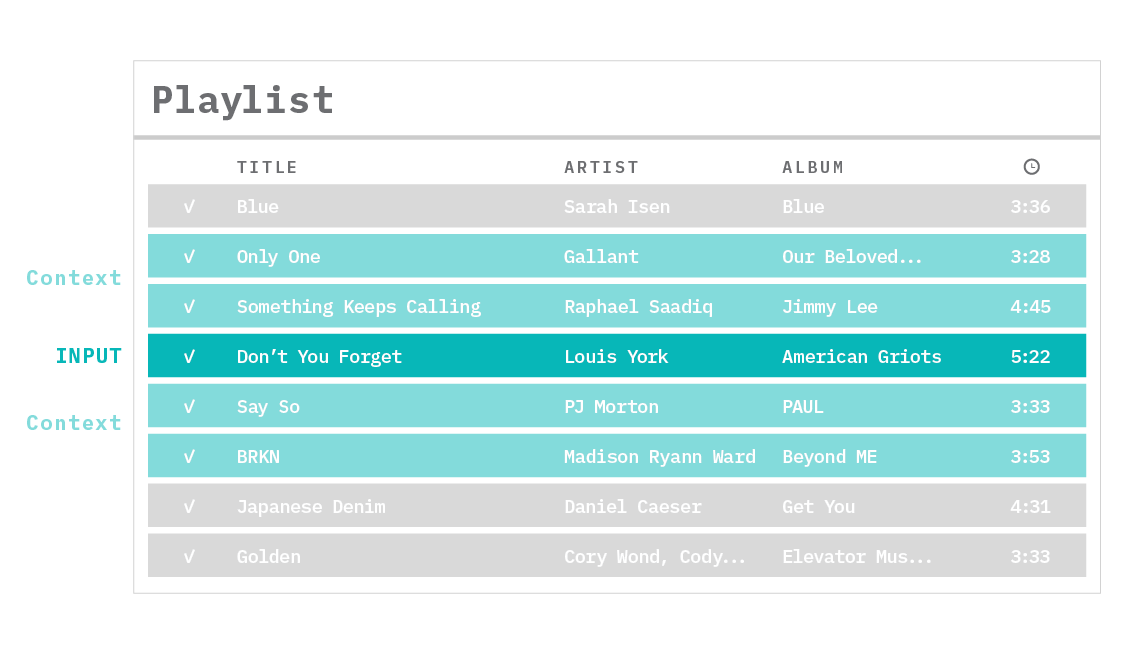

Music recommendations

Recommending additional content that a user might like while they browse through a list of songs can change a user’s experience on a content platform.

The user’s listening queue follows a sequence. For each song the user has listened to in the past, we would want to identify the songs listened to directly before and after it, and use them to teach the machine learning model that those songs somehow belong to the same context. This allows us to find songs that are similar, and provide better recommendations.

Rental recommendations

Another powerful and useful application of session-based recommendation systems occurs in any type of online marketplace. For instance, imagine a website that contains millions of diverse rental listings, and a guest exploring them in search of a place to rent for a vacation. The machine learning model in such a situation should be able to leverage what the guest views during an ongoing search, and learn from these search sessions the similarities between the listings. The similarities learned by the model could potentially encode listing features-like location, price, amenities, design taste, and architecture.

Product recommendations

Leveraging emails in the forms of promotions and purchase receipts to recommend the next item to be purchased has also proven to be a strong purchase intent signal. Again, the idea here is to learn a representation of products from historical sequences of product purchases, under the assumption that products with similar contexts (that is, surrounding purchases) can help recommend more meaningful and diverse suggestions for the next product a user might want to purchase.

Preprocessing

- Filtering

- Remove items with less than 5 interactions

- Remove session than contain only 1 event

- Partition the log into sessions

- Apply 30-minute user inactivity threshold

- Split the data

- Since most datasets consist of time-ordered events, usual cross-validation procedures with the randomized allocation of events across data splits cannot be applied.

- Last day sessions as the test set

- Transformation

- Replace multiple consecutive clicks on the same item by a single click on that item

- For playlist music datasets, we can randomly generate timestamps if not available

Evaluation metrics

- Immediate next-item as the target item

- Hit Rate

- Mean Reciprocal Rank

- All the remaining items of the current session as the target items

- Precision

- Recall

- Mean Average Precision

- Coverage and Popularity bias

Quality factors

- Coverage: how many different items ever appear in the top-k recommendations. This measure represents a form of catalog coverage, which is sometimes referred to as aggregate diversity.

- Popularity bias: High accuracy values can, depending on the measurement method, correlate with the tendency of an algorithm to recommend mostly popular items [Jannach et al. 2015b]. To assess the popularity tendencies of the tested algorithms, we report the average popularity score for the elements of the top-k recommendations of each algorithm. This average score is the mean of the individual popularity scores of each recommended item. We compute these scores based on the training set by counting how often each item appears in one of the training sessions and by then applying min-max normalization to obtain a score between 0 and 1.

- Cold start: Some methods might only be effective when a significant amount of training data is available. We, therefore, report the results of measurements where we artificially removed parts of the (older) training data to simulate such situations.

- Scalability: Training modern machine learning methods can be computationally challenging, and obtaining good results may furthermore require extensive parameter tuning. We, therefore, report the times that the algorithms needed to train the models and to make predictions at runtime. In addition, we report the memory requirements of the algorithms.

References

- M. Ludewig and D. Jannach, 2018. "Evaluation of Session-based Recommendation Algorithms", arXiv. [code].

- M. Quadrana, P. Cremonesi, and D. Jannach, 2018. "Sequence-Aware Recommender Systems", arXiv. [code].

- Predictability Limitsin Session-based Next Item Recommendation

Appendix

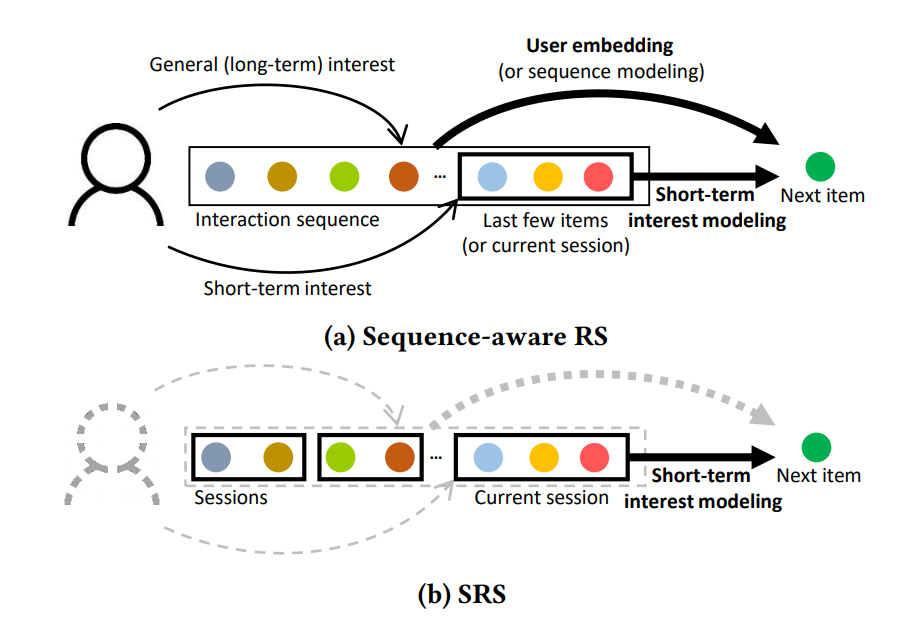

Session-based vs Sequence-aware Recommenders

Short summary of SRS methods

SRSs aim at predicting the next item of each session. Without any user-dependent information, the only information that SRSs can utilize is the chronologically-ordered item sequence in each session which implies the short-term interest of user. Accordingly, some existing methods focus on how to effectively modeling the information in each single session. For example, GRU4Rec uses GRU which takes the embeddings of items in a session as input, to model the sequential patterns in the session. NARM summarizes the hidden states of GRU using an attention module, to model the user’s main purpose and sequential patterns in the session. STAMP incorporates each item information in a session according to its similarity to the last item based on an attention mechanism, to focus on the most recent interest. SASRec uses a self-attention network to capture the user’s preference within a sequence. SR-GNN, which is the first attempt to express the sessions in directed graphs, captures the complex transitions of items in a session via graph neural networks. FGNN introduces an attentional layer and a new readout function in graph neural networks to consider the latent order rather than the chronological item order in a session. RepeatNet first predicts whether the next item will be a repeat consumption or a new item, and then predicts the next item for each case. GRec leverages future data as well when learning the preferences for target items in a session for richer information in dilated convolutional neural networks. However, these methods cannot consider the relationships between sessions, as they use only the information within a single session. To overcome this limitation, some recent methods define the relationships between sessions using the item co-occurrence between them. CSRM incorporates information of the latest few sessions according to their similarity to the current session. CoSAN extends CSRM to find out the similar sessions for each item, not for each session. GCE-GNN, which shows the state-of-the-art recommendation performance, constructs a global graph that models pairwise item-transitions over sessions.