Introduction

It is evident that the pace that technology advances have been increased over the last decades. Scientific discoveries and technological growth introduced to people a huge variety of options and possibilities. One of the most important advantages that technology offers is the direct and easy access to information. Nowadays access to vast networks of information is easy and people can be informed about almost anything they desire. Even though ease of access provided people with the ability to acquire the needed information, they are now facing a new obstacle: this of easily finding what they need. On one hand, information abundance covers the majority of needs but on the other hinders accessibility to information truly valuable to the user. The term that describes this phenomenon is “Information Overload”. Often users are presented with seemingly similar information to their inquiry but irrelevant to their actual needs, rendering this way the discovery of the desired knowledge a difficult task. Continuous expanding of information overload necessitated the development of systems that aim to alleviate such problems. Such systems were introduced in order to filter or retrieve the desired information. Recommendation systems is an example. Recommenders aim to filter out all the unnecessary and irrelevant information and present those that fit the user’s needs. This way the user is relieved of the burden of discovering what he needs making this way information truly accessible.

A recommendation system seeks to understand the user preferences with the objective of recommending him or her items. These systems has become increasingly popular in recent years, in parallel with the growth of internet retailers like Amazon, Netflix or Spotify. Recommender systems are used in a variety of areas including movies, music, news, books, research articles, search queries, social tags, and products in general. In terms of business impact, according to a recent study from Wharton School, recommendation engines can cause a 25% lift in number of views and 35% lift in number of items purchased. So it is worth to understand these systems.

I have a favorite coffee shop I’ve been visiting for years. When I walk in, the barista knows me by name and asks if I’d like my usual drink. Most of the time, the answer is “yes”, but every now and then, I see they have some seasonal items and ask for a recommendation. Knowing I usually order a lightly sweetened latte with an extra shot of espresso, the barista might recommend the dark chocolate mocha — not the fruity concoction piled high with whipped cream and sprinkles. The barista’s knowledge of my explicit preferences and their ability to generalize based on my past choices provides me with a highly-personalized experience. And because I know the barista knows and understands me, I trust their recommendations.

— A happy customer

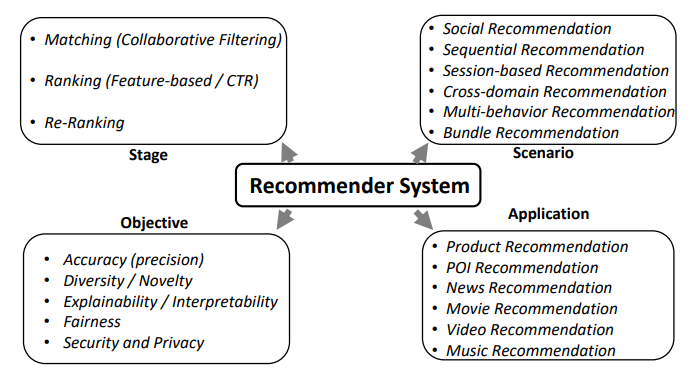

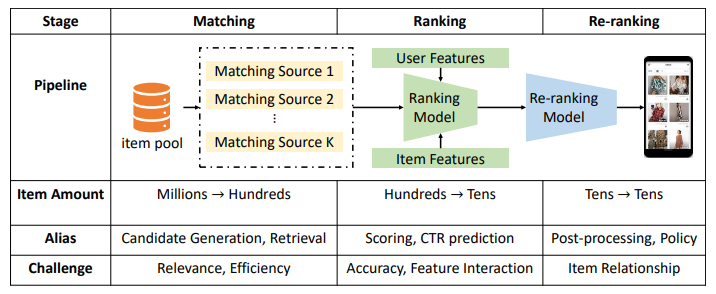

Recommendation systems have been extensively studied by many literature in the past and are ubiquitous in online advertisement, shopping industry/e-commerce, query suggestions in search engines, and friend recommendation in social networks. Moreover, restaurant/music/product/movie/news/app recommendations are only a few of the applications of a recommender system. A small percent improvement on the CTR prediction accuracy has been mentioned to add millions of dollars of revenue to the advertisement industry. Click-Through-Rate (CTR) prediction is a special version of recommender system in which the goal is predicting whether or not a user is going to click on a recommended item. A content-based recommendation approach takes into account the past history of the user's behavior, i.e. the recommended products and the users reaction to them. So, a personalized model that recommends the right item to the right user at the right time is the key to building such a model. On the other hand, the so-called collaborative filtering approach incorporates the click history of the users who are very similar to a particular user, thereby helping the recommender to come up with a more confident prediction for that particular user by leveraging the wider knowledge of users who share their taste in a connected network of users.

Suppose recently I was looking to buy a budget-friendly laptop without having any idea of what to buy. There are possibilities that might waste a lot of time browsing around on the internet and crawling through various sites hoping to find some useful info. I might look for recommendations from other people.

tip

Commercials and recommendations can look similar to the user. Behind the screen, the intent of the content is different; a recommendation is calculated based on what the active user likes, what others have liked in the past, and what’s often requested by the receiver. A commercial is given for the benefit of the sender and is usually pushed on the receiver. The difference between the two can become blurry.

Recommenders work by collecting information — by noting what you ask for — such as what movies you tell your video streaming app you want to see, ratings and reviews you’ve submitted, purchases you’ve made, and other actions you’ve taken in the past. Perhaps more importantly, they can keep track of choices you’ve made: what you click on and how you navigate. How long you watch a particular movie, for example. Or which ads you click on or which friends you interact with. All this information is streamed into vast data centers and compiled into complex, multidimensional tables that quickly balloon in size. They can be hundreds of terabytes large — and they’re growing all the time. That’s not so much because vast amounts of data are collected from any one individual, but because a little bit of data is collected from so many. In other words, these tables are sparse — most of the information most of these services have on most of us for most of these categories is zero. But, collectively these tables contain a great deal of information on the preferences of a large number of people. And that helps companies make intelligent decisions about what certain types of users might like.

The rapid growth of data collection has led to a new era of information. Data is being used to create more efficient systems and this is where Recommendation Systems comes into play. Recommendation Systems are a type of information filtering system as they improve the quality of search results and provide items that are more relevant to the search item or related to the search history of the user. They are used to predict the rating or preference that a user would give to an item. Companies like Netflix and Spotify depend highly on the effectiveness of their recommendation engines for their business and success

In reality, because these systems capture so much data, from so many people, and are deployed at such an enormous scale, they’re able to drive tens or hundreds of millions of dollars of business with even a small improvement in the system’s recommendations. A business may not know what any one individual will do, but thanks to the law of large numbers, they know that, say, if an offer is presented to 1 million people, 1 percent will take it. But while the potential benefits from better recommendation systems are big, so are the challenges. Successful internet companies, for example, need to process ever more queries, faster, spending vast sums on infrastructure to keep up as the amount of data they process continues to swell. Companies outside of technology, by contrast, need access to ready-made tools so they don’t have to hire whole teams of data scientists. If recommenders are going to be used in industries ranging from healthcare to financial services, they’ll need to become more accessible.

In the last decade, the Internet has evolved into a platform for large-scale online services, which profoundly changed the way we communicate, read the news, buy products, and watch movies. In the meanwhile, the unprecedented number of items (we use the term item to refer to movies, news, books, and products.) offered online requires a system that can help us discover items that we preferred. Recommender systems are therefore powerful information filtering tools that can facilitate personalized services and provide tailored experiences to individual users. In short, recommender systems play a pivotal role in utilizing the wealth of data available to make choices manageable.

— d2lAI

Why companies implement Recommendation Systems

- Improve retention: Continuously catering to users’ preferences makes them more likely to remain loyal subscribers of the service

- Increase sales: Various research shows an increase in upselling revenue ranging from 10-50% caused by accurate “You must also like” product recommendations

- Form habits: Serving accurate content can trigger cues, building strong habits and influencing usage patterns in customers

- Accurate work: Analysts can save up to 80% time when served tailored suggestions for materials necessary for their further research.

note

The biggest players use recommendation engines to boost sales, increase revenue, and improve customer experience. They have experimented with recommenders and worked out the best ways to use them, so now businesses all around the world can learn from them and follow their lead. Though you may not necessarily be the next Netflix, a recommender system can be perfectly suited to your business needs – and it should, as using any AI technology should be done strategically, and not in an attempt to blindly follow a market leader.

Problem Statement

A typical recommender system takes the training sample in the form: , where denotes the index of the sample in the whole dataset. The ID type feature is the sparse encoding of large-scale categorical information. For example, one may use a group of unique integers to record the microvideos (e.g., noted as ⟨VideoIDs⟩) that have been viewed by a user; similar ID type features may include location (⟨LocIDs⟩), relevant topics (⟨TopicIDs⟩), followed video bloggers (⟨BloggerIDs⟩), etc. In our formalization, x ID is the collection of all ID type features—for the above example, it can be considered as:

The Non-ID type feature can include various visual or audio features. And the label may include one or multiple value(s) corresponding to one or multiple recommendation task(s). The parameter of the recommender system usually has two components:

We use to denote the concatenation of all embedding vectors that has correspondence in ; to denote a function parameterized by implemented by a deep neural network that takes the looked up embeddings and Non-ID features as input and generates the prediction.

The recommender system predicts one or multiple values by :

The training system essentially solves the following optimization:

If we use to denote some loss functions over the prediction and true label(s) , can be materialized as:

The gradients will be:

Lastly, we use the following updating rule:

Scope

Process

Design and Manage Experiments

To leverage the continuous improvement potential of recommendation engines, it is necessary to experiment with different strategies within a sound framework. When designing a prediction model for a recommendation engine, the data scientist might well focus on a simple strategy, such as predicting the probability that a given customer clicks on a given recommendation.

info

Most companies aren’t too keen about telling the world how they track behavior or monitor performance, mainly because it can be a business disadvantage and it can give hackers hints as to what weaknesses the company could have. In addition, if your users know too many intimate details of your recommender system algorithm, the user’s behavior could become less spontaneous. This could induce biases in the results or even make users do things to push certain recommendations in a specific direction.

This may seem a reasonable compromise compared to the more precise approach of trying to gather information about whether the customer purchased the product and whether to attribute this purchase to a given recommendation. However, this is not adequate from a business perspective, as phenomena like cannibalization may occur (i.e., by showing a low-margin product to a customer, one might prevent them from buying a high-margin product). As a result, even if the predictions were good and resulted in increased sales volume, the overall revenue might be reduced.

On the other hand, bluntly promoting the organization’s interest and not the customer’s could also have detrimental long-term consequences. The overarching KPI that is used to assess if a given strategy yields better results should be carefully chosen, together with the time period over which it is evaluated. Choosing the revenue over a two-week period after the recommendation as the main KPI is common practice.

To be as close as possible to an experimental setting, also called A/B testing, the control group and the experimental groups have to be carefully chosen. Ideally, the groups are defined before the start of the experiment by randomly splitting the customer base. If possible, customers should not have been involved in another experimentation recently so that their historical data is not polluted by its impact. However, this may not be possible in a pull setting in which many new customers are coming in. In this case, the assignment could be decided on the fly. The size of the groups as well as the duration of the experiments depend on the expected magnitude of the KPI difference between the two groups: the larger the expected effect, the smaller the group size and the shorter the duration.

The experimentation could also be done in two steps: in the first one, two groups of equal but limited size could be selected. If the experimentation is positive, the deployment could start with 10% on the new strategy, a proportion that can be raised progressively if results are in line with expectations.

tip

Think the process as a team-sport.

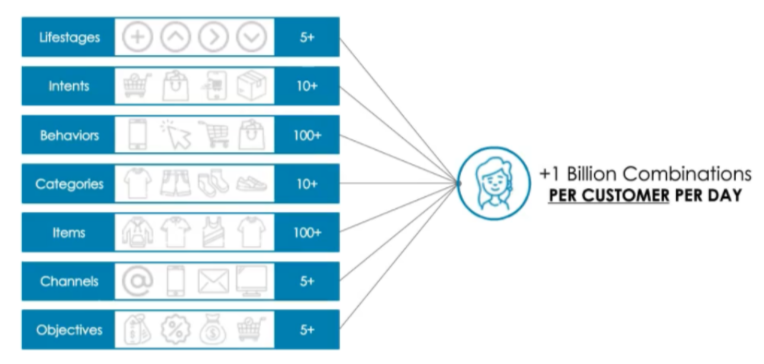

Sometimes the personalized, sometimes the non-personalized recommendations entail more conversions, therefore professional recommendation engines have to make thousands of decisions in every second: ‘does this customer have enough history here to get personalized offers that might imply higher probability for conversion or shall we ignore the user’s profile and apply general item-to-item recommendations?’- This decision type (fallback scenario) is the most often used by recommendation engines.

Data Processing

The customer data that is usually accessible to a recommendation engine is composed of the following:

- Structural information about the customer (e.g., age, gender, location)

- Information about historical activities (e.g., past views, purchases, searches)

- Current context (e.g., current search, viewed product)

A good product recommendation engine shall easily use the below data to display a solid list of recommended products:

- Clickstream behaviour: Views, likes, shopper behaviours like ‘add to favorite’ and ‘add to cart’

- Transactions: Date, time, amount, price of the order along with the customer ID

- Stock data: Size, color, model etc. based stock movements

- Social media data: In the case that unstructured data can be matched with a single user

- Customer reviews data: If product reviews are present can be boiled down to product specs

- Retailer’s commercial priorities: Brands/models that should be displayed in the product recommendation set

- Customer lifetime value: Recency, frequency and monetary value of customers

- Popular products: Products with high turnover rate

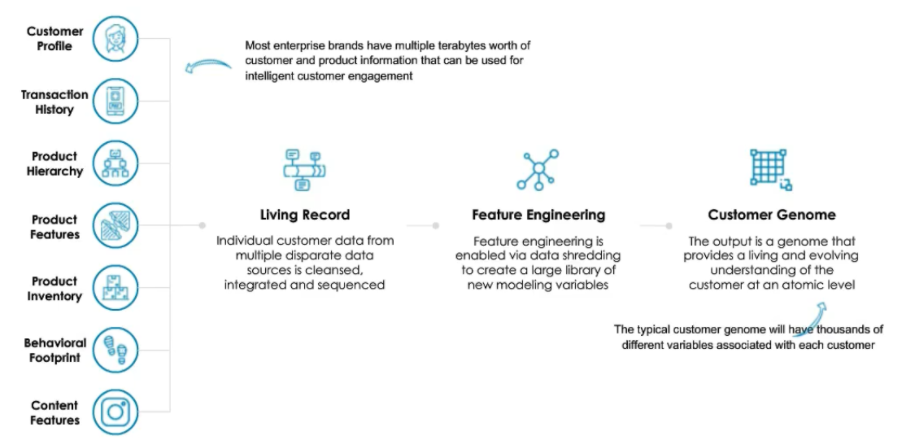

Data integration and transformation is the first step to enable decision intelligence at the individual customer-level.

Whatever the technique used, all customer information has to be aggregated into a vector (a list of fixed size) of characteristics. For example, from the historical activities, the following characteristics could be extracted:

- Amount of purchases during the last week or the last month

- Number of views during past periods

- Increase in spending or in views during the last month

- Previously seen impressions and customer’s response

trend

Earlier in the days of Netflix prize, most of the recommender systems were based on explicit data(ratings data) where users explicitly give ratings to express their opinion. A lot has changed since then. With enhancements in data collection techniques and decrease in the trend of giving explicit ratings among customers, implicit feedback data has become more popular in both academia and industries to build robust recommender systems.

In addition to customer data, the recommendation context can also be taken into account. For example, days to summer for seasonal products like above-ground swimming pools or days to monthly pay day, as some customers delay purchases for cash flow reasons.

Once the customer and context data is formatted, it is important to define the set of possible recommendations, and there are many choices to make. The same product may be presented with different offers, which may be communicated in different ways.

info

Recommendation lists are generated based on user preferences, item features, user-item past interactions, and some other additional information such as temporal (e.g., sequence-aware recommender) and spatial (e.g., POI recommender) data.

It is of the utmost importance not to forget the “do not recommend anything” option. Indeed, most of us have the personal experience that not all recommendations have a positive impact. Sometimes not showing anything might be better than the alternatives. It’s also important to consider that some customers may not be entitled to see certain recommendations, for example depending on their geographical origin.

Baseline performance

caution

Making recommender systems is such fun that you might not care, but the people who’re paying you will want to know if the recommender has any effect.

Once we train a model and get results from evaluation metrics we choose, we will wonder how should we interpret the metrics or even wonder if the trained model is better than a simple rule-based model. Baseline results help us to understand those. Let's say we are building a food recommender. We evaluated the model on the test set and got nDCG (at 10) = 0.3. At that moment, we would not know if the model is good or bad. But once we find out that a simple rule of 'recommending top-10 most popular foods to all users' can achieve nDCG = 0.4, we see that our model is not good enough. Maybe the model is not trained well, or maybe we should think about if nDCG is the right metric for prediction of user behaviors in the given problem.

Most importantly, different baseline approaches should be taken for different problems and business goals. For example, recommending the previously purchased items could be used as a baseline model for food or restaurant recommendation since people tend to eat the same foods repeatedly. For TV show and/or movie recommendation, on the other hand, recommending previously watched items does not make sense. Probably recommending the most popular (most watched or highly rated) items is more likely useful as a baseline.

tip

One thing to consider when exploring and cleaning your data for a recommendation system, in particular, is changing user tastes. Depending on what you’re recommending, the older reviews, actions, etc., may not be the most relevant on which to base a recommendation. Consider only looking at features that are more likely to represent the user’s current tastes and removing older data that might no longer be relevant or adding a weight factor to give more importance to recent actions compared to older ones.

Recent work has demonstrated a wide variety of efficient approaches for building recommendation systems, utilizing either collaborative filtering, content-based filtering, context-based filtering, knowledge-based inferencing or hybrid filtering. Collaborative filtering (CF) is considered as the most basic, mature, popular, and the easiest of methods to find recommendations based on historical reviews of user and item interactions. Simon Funk published a detailed implementation of a regularized matrix factorization (MF) based collaborative filtering approach, known as “Funk SGD” in his blog. Paterek introduced a bunch of novel techniques, including MF with biases, applying kernel ridge regression on the residual of MF, linear model for each item, and asymmetric factor models for collaborative filtering. Zhou et al. and Fredrickson have described the Alternating Least Squares (ALS) algorithm to address the performance bottlenecks associated with the Gradient Descent (SGD) and Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) based approaches for MF. Collaborative recommender systems have been implemented in different application areas. GroupLens is a news-based architecture employing collaborative methods in assisting users to locate articles from massive news database. Content-based filtering (CBF) recommends items based on the similarity between the preferences of the current user (properties of items already investigated by the user) and item properties extracted from item descriptions. Incorporating contextual information in a recommender system helps to get a clearer picture of the situation of any individual, place or object, which is of relevance to the system for prediction. Knowledge-based recommendation attempts to suggest objects based on inferences about a user’s needs and preferences. Hybrid recommender systems combine two or more filtering techniques in different ways to increase the accuracy and performance of recommender systems. These techniques combine multiple filtering approaches in order to harness their strengths while leveling out their corresponding weaknesses. One of the first was Fab, which incorporated a combination of CF, to find users having similar website preferences, with CBF to find websites with similar content. The work of Burke was one of the first qualitative surveys on hybrid recommender systems, which can be classified, based on their operations, into weighted hybrid, mixed hybrid, switching hybrid, feature combination hybrid, cascade hybrid, feature-augmented hybrid and meta-level hybrid.

Key factors to consider

Some of the many factors to consider include:

- What business goals and metrics are used to evaluate the effectiveness of the system? Besides the usual metrics such as precision@k and coverage, others to consider include diversity, serendipity, and novelty (as discussed in preceding paragraphs).

- How to address the cold start problem for new users or new items?

- What is the desired latency for predictions (and possibly how much training time is acceptable)? This depends on model complexity.

- Scalability and what kind of hardware (instance type in AWS terms) are required to support training and serving the models effectively? Again, this depends on model complexity, and will be a substantial factor in the cost of the solution.

- How interpretable is the model? This may be a key requirement for business stakeholders.

Design considerations

Deep learning for recommendations

- Deep learning can model the non-linear interactions in the data with non-linear activations such as ReLU, Sigmoid, Tanh… This property makes it possible to capture the complex and intricate user-item interaction patterns. Conventional methods such as matrix factorization and factorization machines are essentially linear models. This linear assumption, acting as the basis of many traditional recommenders, is oversimplified and will greatly limit their modeling expressiveness. It is well-established that neural networks are able to approximate any continuous function with arbitrary precision by varying the activation choices and combinations. This property makes it possible to deal with complex interaction patterns and precisely reflect the user’s preference.

- Deep learning can efficiently learn the underlying explanatory factors and useful representations from input data. In general, a large amount of descriptive information about items and users is available in real-world applications. Making use of this information provides a way to advance our understanding of items and users, thus, resulting in a better recommender. As such, it is a natural choice to apply deep neural networks to representation learning in recommendation models. The advantages of using deep neural networks to assist representation learning are in two-folds: (1) it reduces the efforts in hand-craft feature design; and (2) it enables recommendation models to include heterogeneous content information such as text, images, audio, and even video.

- Deep learning is powerful for sequential modeling tasks. In tasks such as machine translation, natural language understanding, speech recognition, etc., RNNs and CNNs play critical roles. They are widely applicable and flexible in mining sequential structure in data. Modeling sequential signals is an important topic for mining the temporal dynamics of user behavior and item evolution. For example, next-item/basket prediction and session-based recommendations are typical applications. As such, deep neural networks become a perfect fit for this sequential pattern mining task.

- Deep learning possesses high flexibility. There are many popular deep learning frameworks nowadays, including TensorFlow, Keras, Caffe, MXnet, DeepLearning4j, PyTorch, Theano… These tools are developed in a modular way and have active community/professional support. The good modularization makes development and engineering a lot more efficient. For example, it is easy to combine different neural structures to formulate powerful hybrid models or replace one module with others. Thus, we could easily build hybrid and composite recommendation models to simultaneously capture different characteristics and factors.

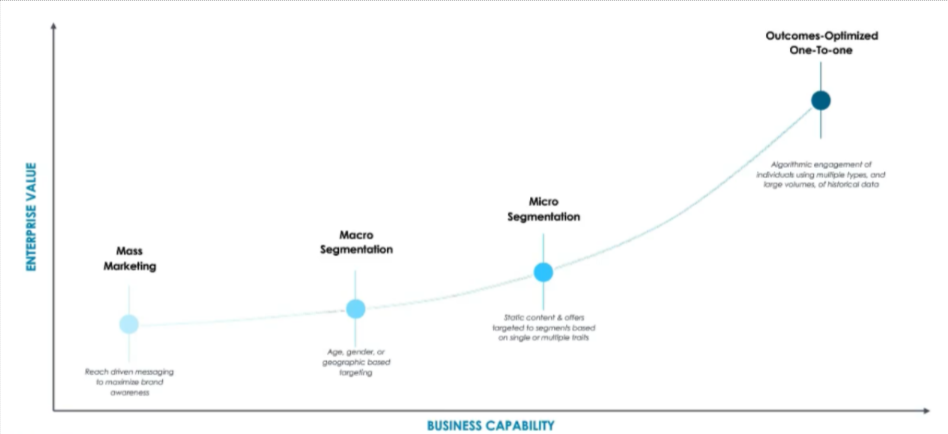

The evolution of personalization