Processes

Retrieval and Ranking

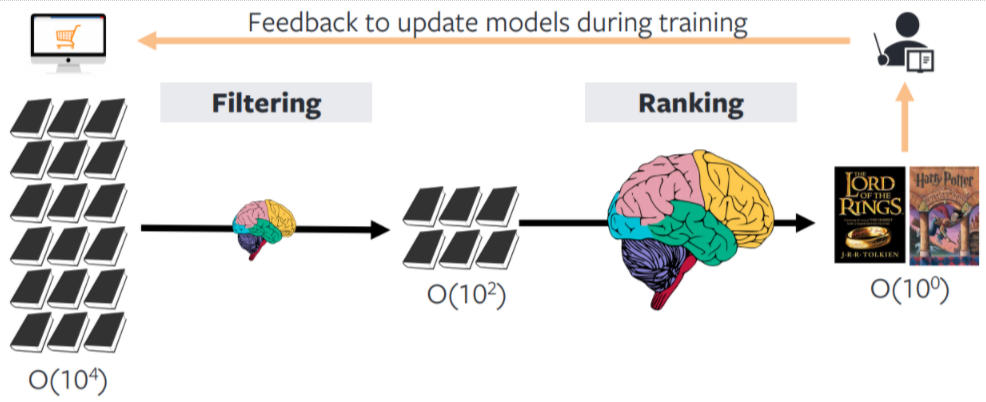

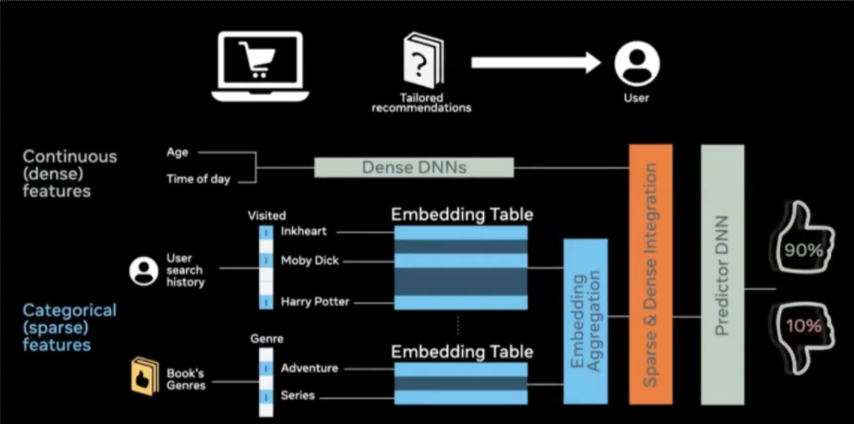

Recommender systems aim to filter information for users, which has become one kind of fundamental service in today’s information platforms. Generally, from the perspective of real-world application, the recommender systems contain two stages, matching and ranking. Recently, deep learning has become the state-of-the-art solution of recommender systems in both two stages.

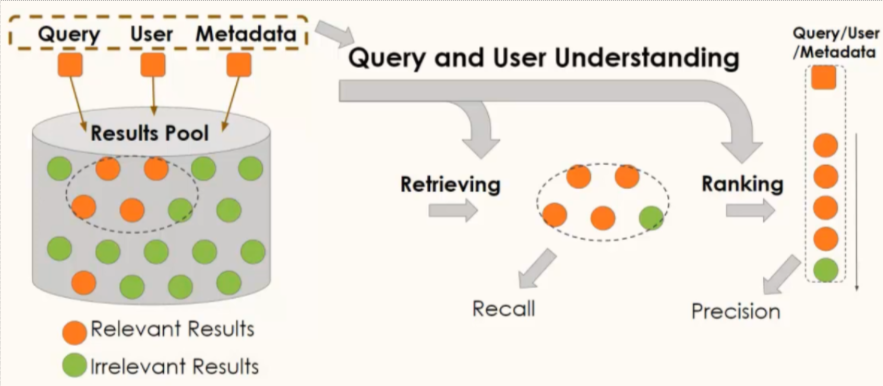

The matching (a.k.a. retrieval) stage, of which the mainstream methods are collaborative filtering, learns user interests from historical behaviors, deep neural networks methods, or even graph neural networks, achieve promising performance. It is responsible for selecting an initial set of hundreds of candidates from all possible candidates. The main objective of this model is to efficiently weed out all candidates that the user is not interested in. Because the retrieval model may be dealing with millions of candidates, it has to be computationally efficient.

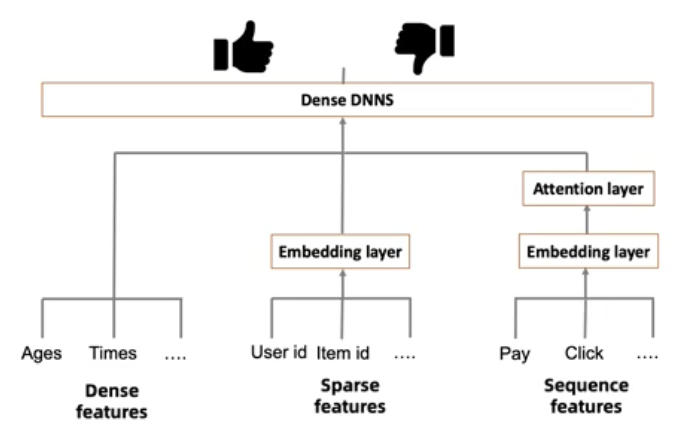

The ranking stage, which is also known as click-through rate (CTR) prediction, deep learning-based models such as DeepFM with multilayer perceptron, xDeepFM with compressed interaction network, DIN with attention mechanisms, etc., are demonstrated effective in learning from complex features of users and items. The ranking stage takes the outputs of the retrieval model and fine-tunes them to select the best possible handful of recommendations. Its task is to narrow down the set of items the user may be interested in to a shortlist of likely candidates.

Candidate generation is a fast—but coarse—approach to get (hundreds of) item candidates from millions of items. We trade off precision for efficiency to reduce the search space (e.g., from 100 million to 1,000 candidates, a 99.999% reduction). This is usually done via metadata-based filters (e.g., category, brand) or k-nearest neighbors.

Ranking is a slower—but more precise—approach to sort and select top recommendation candidates. We have leeway to include features that might not have been feasible in the candidate generation step. Such features include user persona (e.g., demographics, price propensity), item metadata (e.g., attributes, engagement statistics), cross features (e.g., interaction between each feature pair), and media embeddings.

Retrieval

Retrieval models are often composed of two sub-models:

- A query model computing the query representation (normally a fixed-dimensionality embedding vector) using query features.

- A candidate model computing the candidate representation (an equally-sized vector) using the candidate features

The outputs of the two models are then multiplied together to give a query-candidate affinity score, with higher scores expressing a better match between the candidate and the query.

- The representation stage creates a vector representation of all 3 kinds of data - users, items and context. It can be done offline.

- The retrieval stage is responsible for selecting an initial set of hundreds of candidates from all possible candidates. The main objective of this model is to efficiently weed out all candidates that the user is not interested in. Because the retrieval model may be dealing with millions of candidates, it has to be computationally efficient.

The system starts from a potentially huge corpus and generates a much smaller subset of candidates. For example, the candidate generator in YouTube reduces billions of videos down to hundreds or thousands. The model needs to evaluate queries quickly given the enormous size of the corpus. A given model may provide multiple candidate generators, each nominating a different subset of candidates.

Ranking

Ranking can be framed as either a classification or learning to rank problem. As a classification problem, we can score candidates based on probability of click or purchase. Logistic regression with crossed features is simple to implement and a difficult baseline to beat. Decision trees are also commonly used. As a learning to rank problem, commonly used algorithms include LambdaMart, XGBoost, and LightGBM. Neural networks are also gaining adoption, thanks to gains in model efficiency via distillation, pruning, quantization, etc.

Beyond Retrieval and Ranking

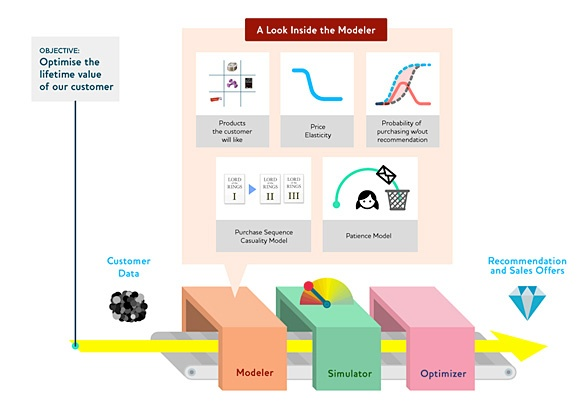

The following framework represent an advanced version of the retrieval ranking framework.

](/recohut/assets/images/content-concepts-raw-processes-untitled-2-d882169676e8f76267aa09fb8df8b35b.png)

source: Moving Beyond Recommender Models

The offline environment largely hosts batch processes such as model training (e.g., representation learning, ranking), creating embeddings for catalog items, and building an approximate nearest neighbors (ANN) index or knowledge graph to find similar items. It may also include loading item and user metadata into a feature store that is used to augment input data during ranking.

The online environment then uses the artifacts generated in the offline environment (e.g., ANN indices, knowledge graphs, models, feature stores) to serve individual requests. A typical approach is converting the input item or search query into an embedding, followed by candidate retrieval and ranking. There are also other preprocessing steps (e.g., standardizing queries, tokenization, spell check) and post-processing steps (e.g., filtering undesirable items, business logic) though we won’t be discussing them in this writeup.

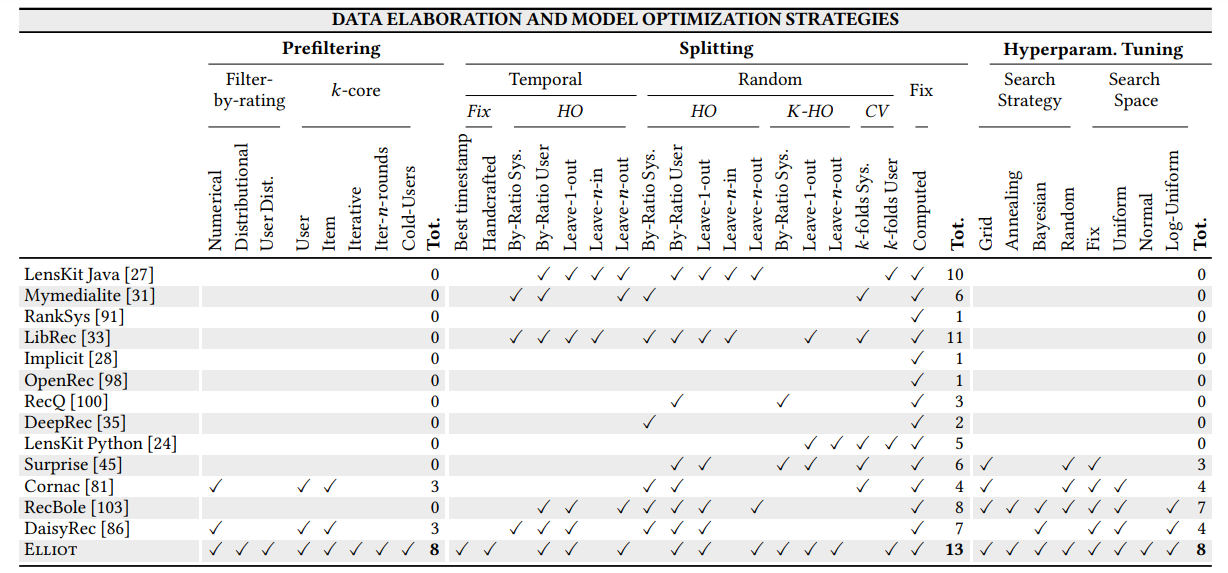

Prefiltering, Splitting and Hyperparameter Tuning Process

Source - Elliot.

Industrial Examples

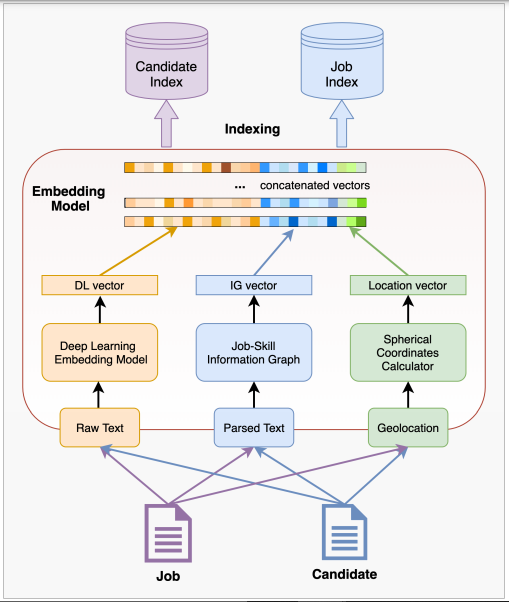

CareerBuilder

](/recohut/assets/images/content-concepts-raw-processes-untitled-4-c0b23bc9a085b15fef652b8333b17b55.png)

The Architecture of the two-stage online recruitment recommender system. source: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2107.00221.pdf

Fused-embedding model with vectors from deep learning embedding model (DLEM), skill-job information graph, and geolocation calculator.

Weibo

stack for real-time recsys](/recohut/assets/images/content-concepts-raw-processes-untitled-6-94bb57017f3dc7778791be1f9eabfaf2.png)

Weibo stack for real-time recsys

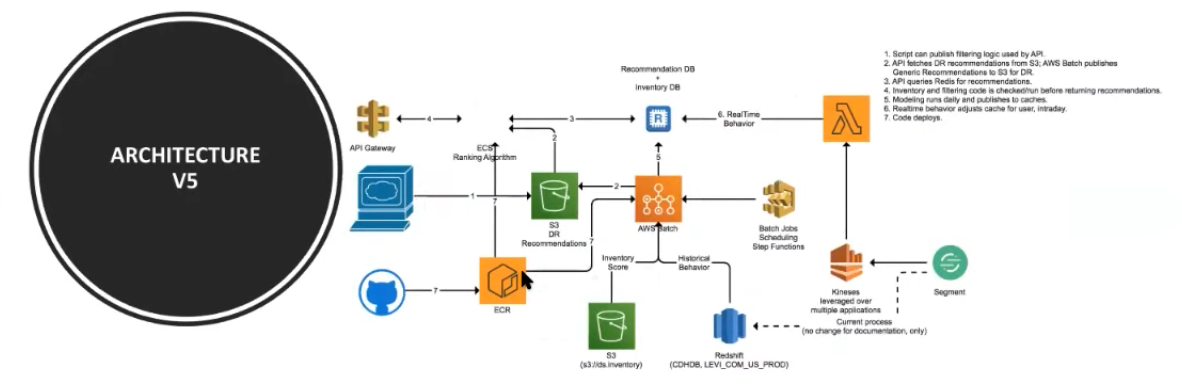

Levis

Levi's

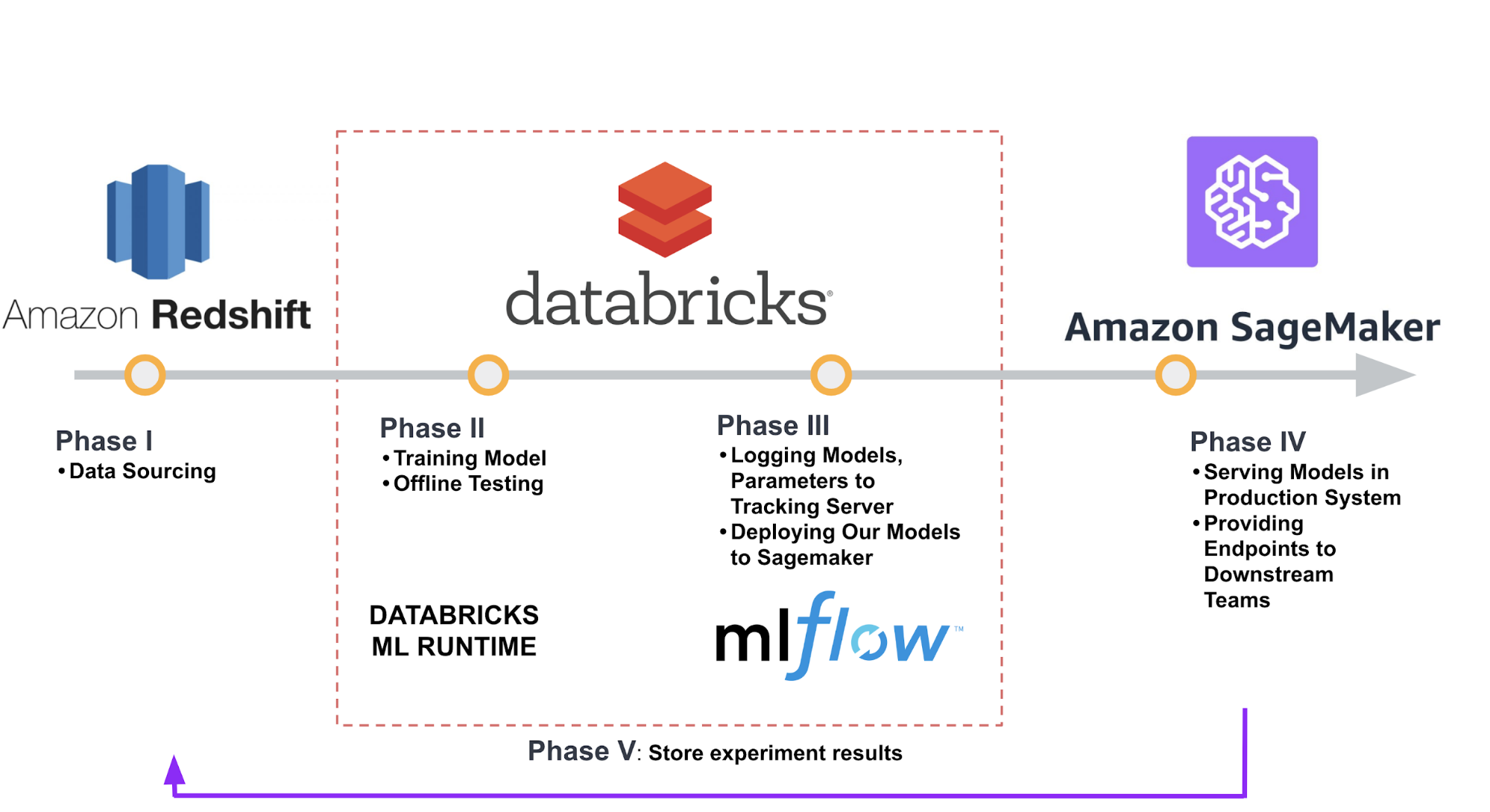

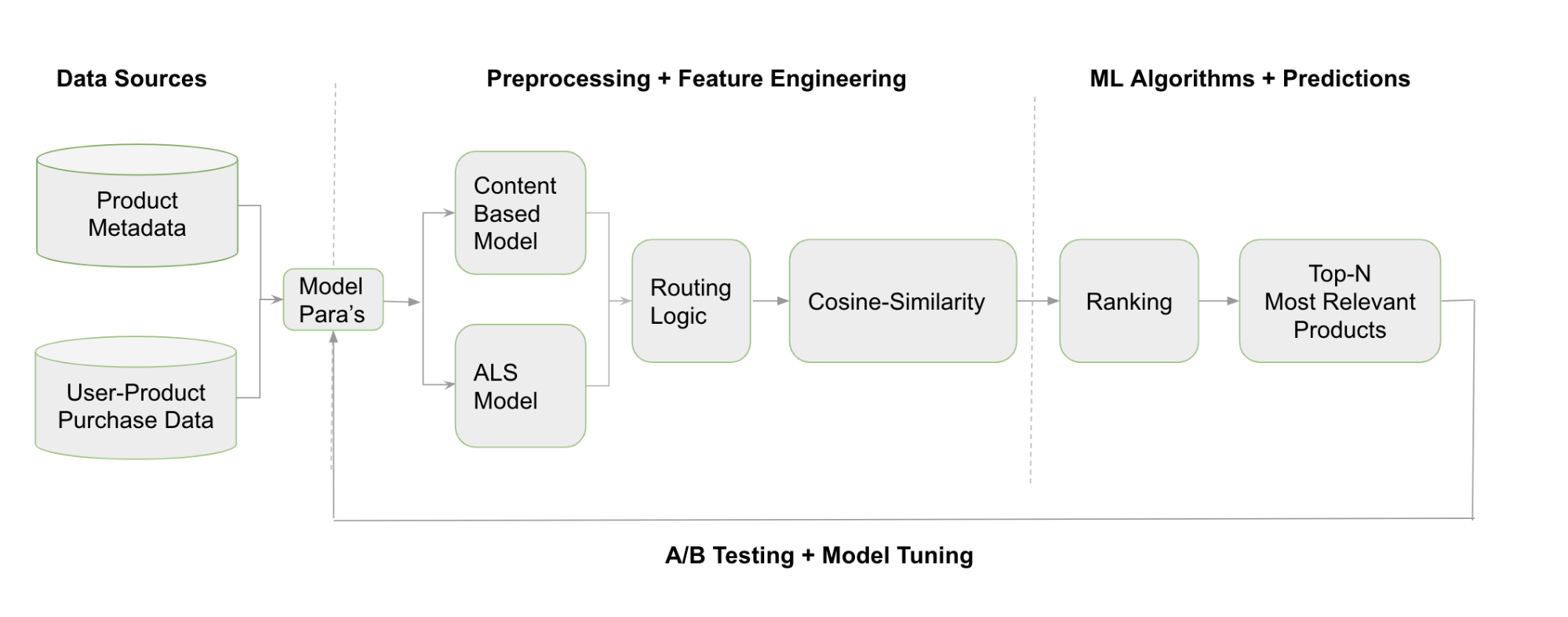

Brandless

Brandless

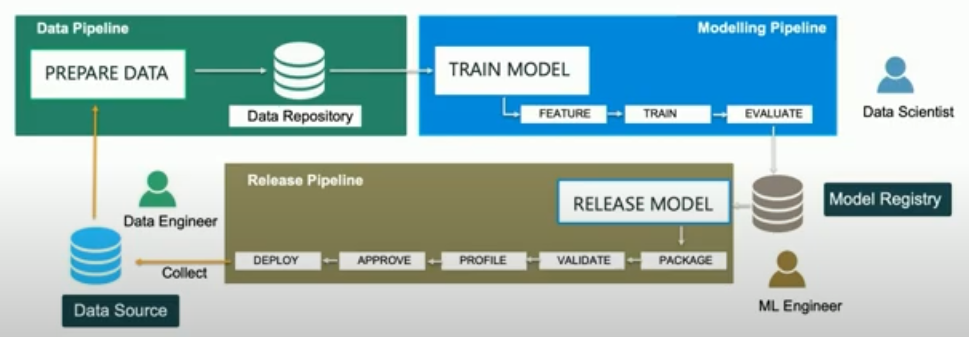

End-to-end machine learning workflow at Brandless.

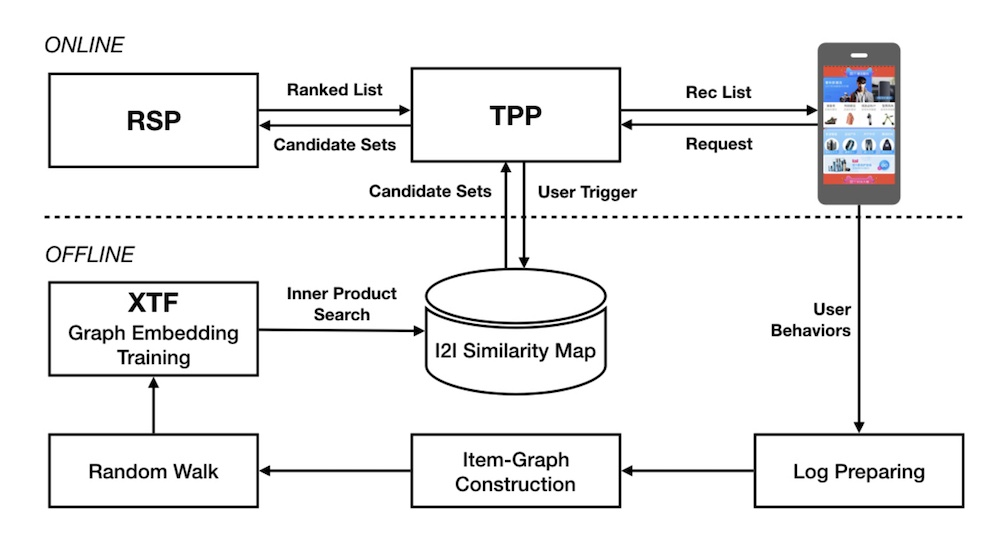

Alibaba Retrieval

In building item embeddings for candidate retrieval, Alibaba shared the process. In the offline environment, session-level user-item interactions are mined to construct a weighted, bidirectional item graph. Then, item sequences are generated via random walks on the graph. Item embeddings are then learned via representation learning (i.e., word2vec skip-gram), doing away with the need for labels. Finally, with the item embeddings, they get the nearest neighbor for each item and store it in their item-to-item (i2) similarity map (i.e., a key-value store).

Alibaba's design for candidate retrieval in Taobao via item embeddings and ANN.

In the online environment, when the user launches the app, the Taobao Personalization Platform (TPP) starts by getting the latest items that the user interacted with (e.g., click, like, purchase). These items are then used to retrieve candidates from the i2i similarity map. The candidates are then passed to the Ranking Service Platform (RSP) for ranking via a deep neural network, before being displayed to the user.

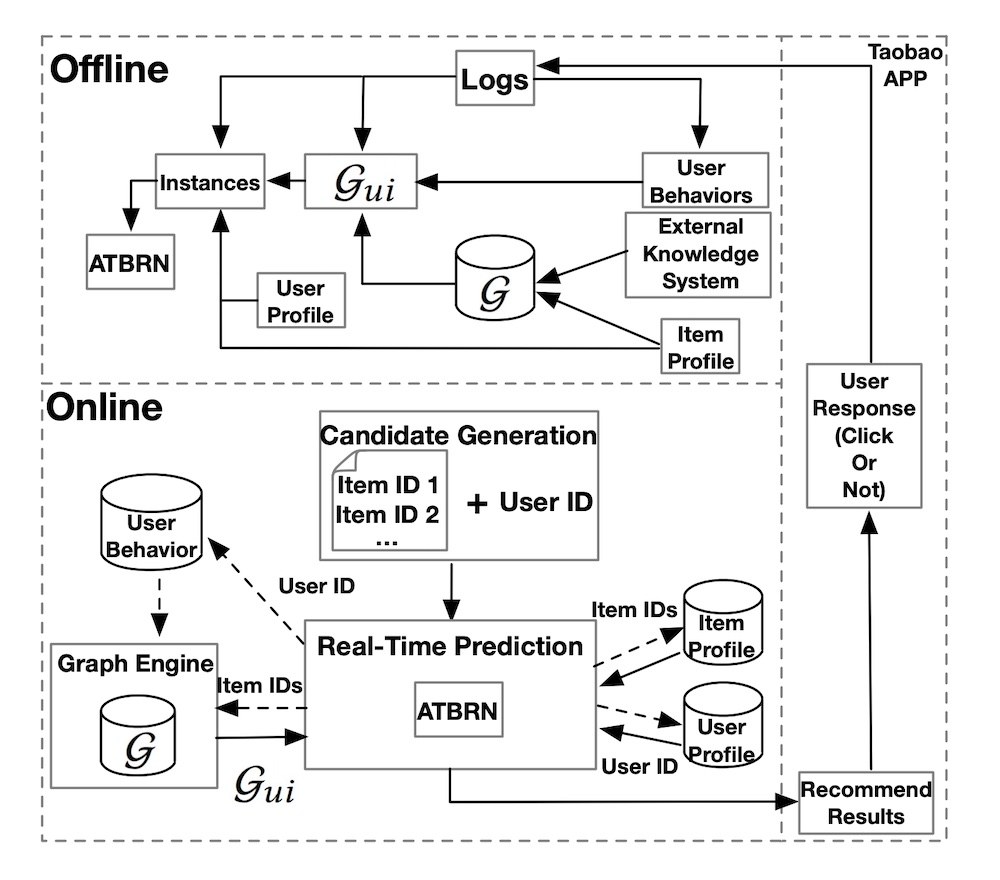

Alibaba Ranking

Alibaba also shared a slightly different example where they apply a graph network for ranking. In the offline environment, they combine an existing knowledge graph (G), user behavior (e.g., impressed but not clicked, clicked), and item metadata to create an adaptive knowledge graph (G_ui). This is then merged with user metadata (e.g., demographics, user-item preferences) to train the ranking model (Adaptive Target-Behavior Relational Graph Network, ATBRN).

Alibaba's design for ranking in Taobao via a graph network (ATBRN).

In the online environment, given a user request, the candidate generator will retrieve a set of candidates and the user ID, before passing them to the Real-Time Prediction (RTP) platform. RTP then queries the knowledge graph with the item IDS and fetches item and user metadata from the feature stores. The graph representations, item metadata, and user metadata is then fed into the ranking model (i.e., ATBRN) to predict the probability of click on each candidate item. The candidates are then reordered based on probability and displayed to the user.

JD

](/recohut/assets/images/content-concepts-raw-processes-untitled-12-16c17acdf1ed4e231b37c8a6bec22a87.png)

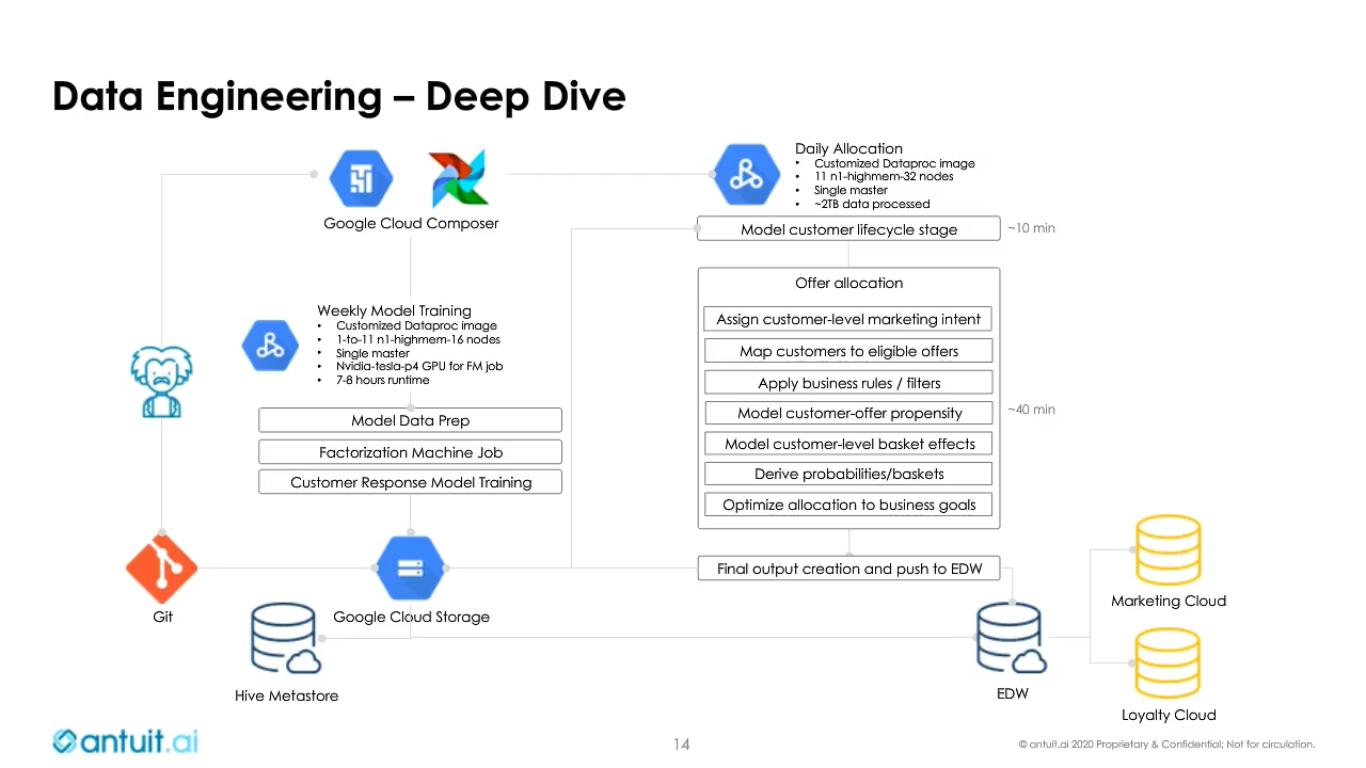

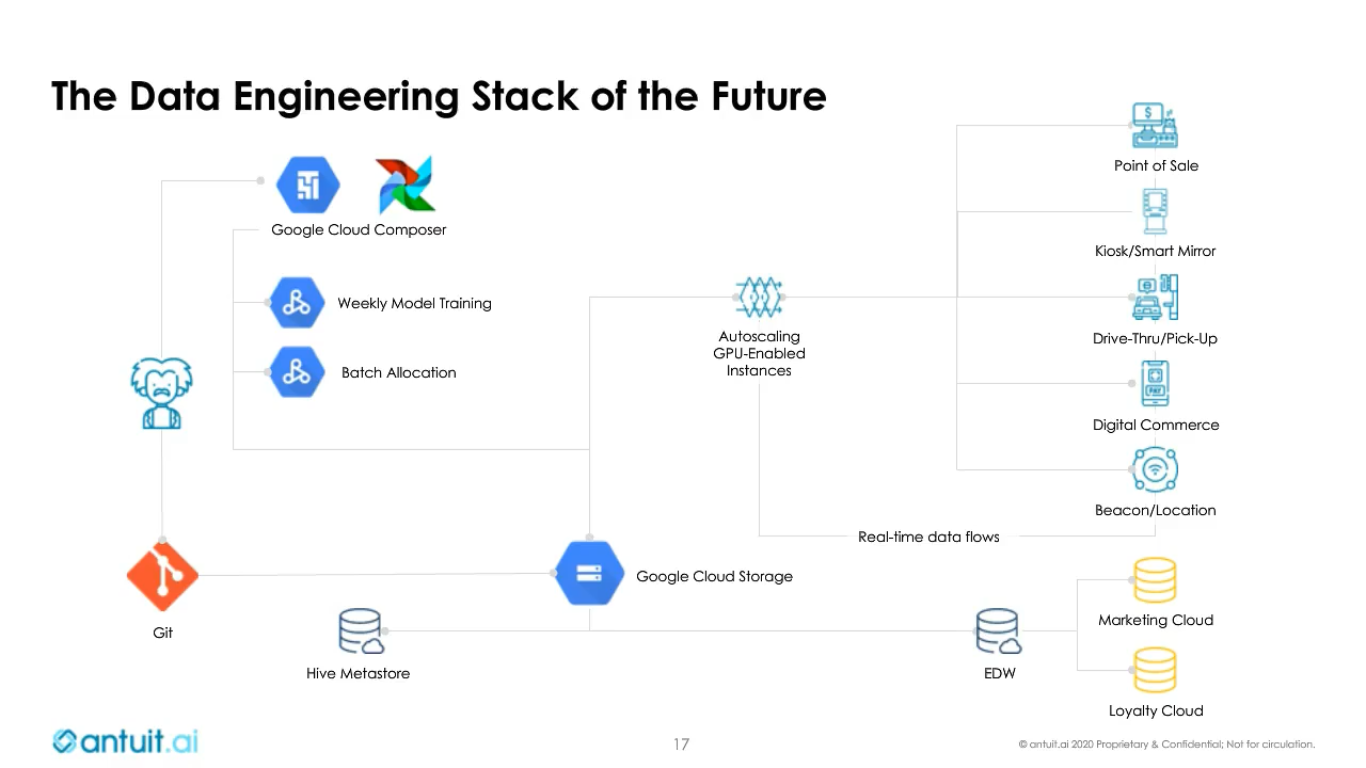

Antuit

antuit.ai

Tools and Service Processes

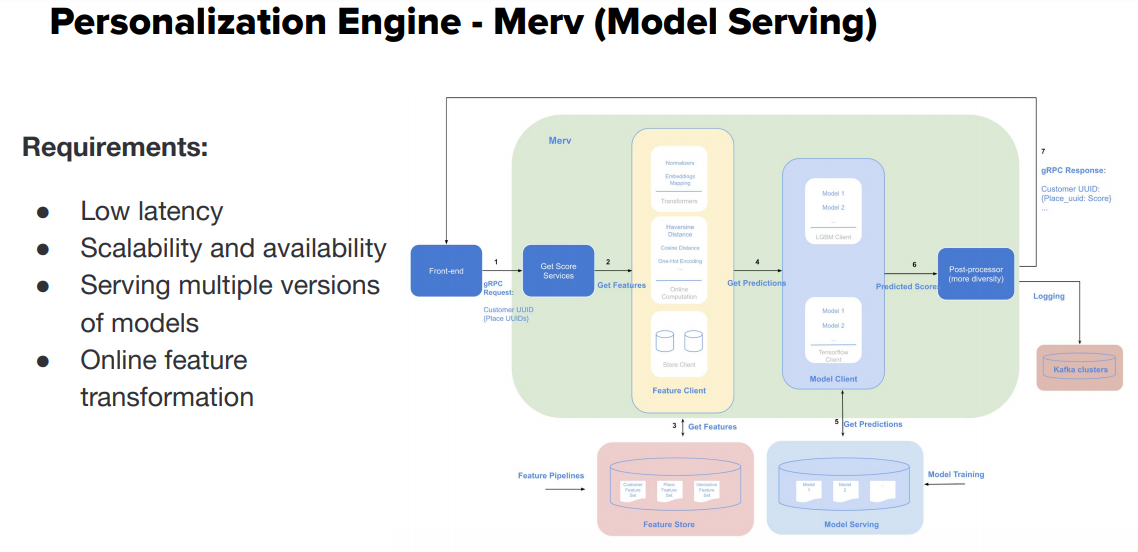

Merv Personalization Engine for Model Serving

Merv

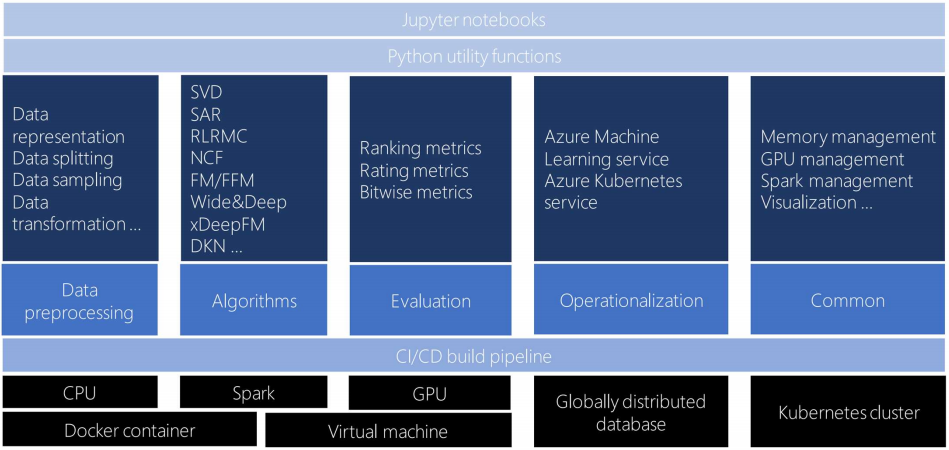

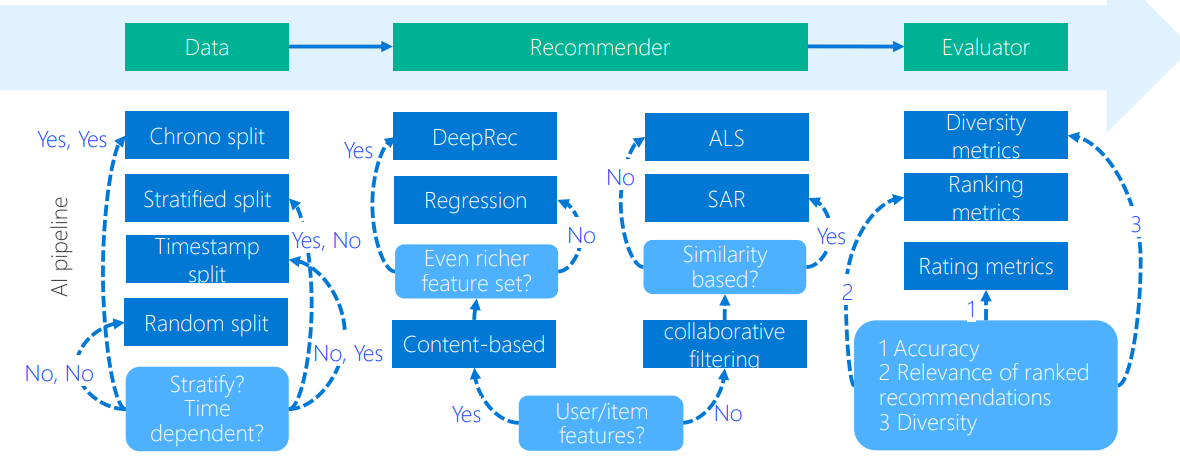

Microsoft Recommender Toolkit

Microsoft recommenders toolkit

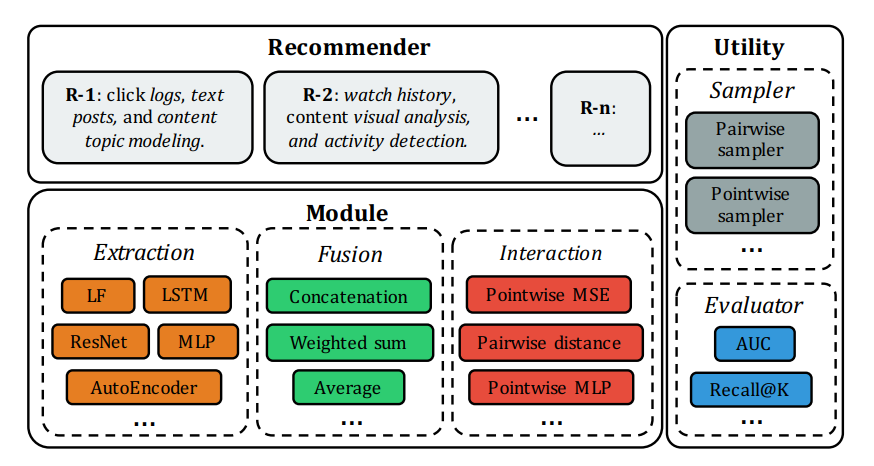

OpenRec

OpenRec

Amazon Personalize

Amazon Personalize

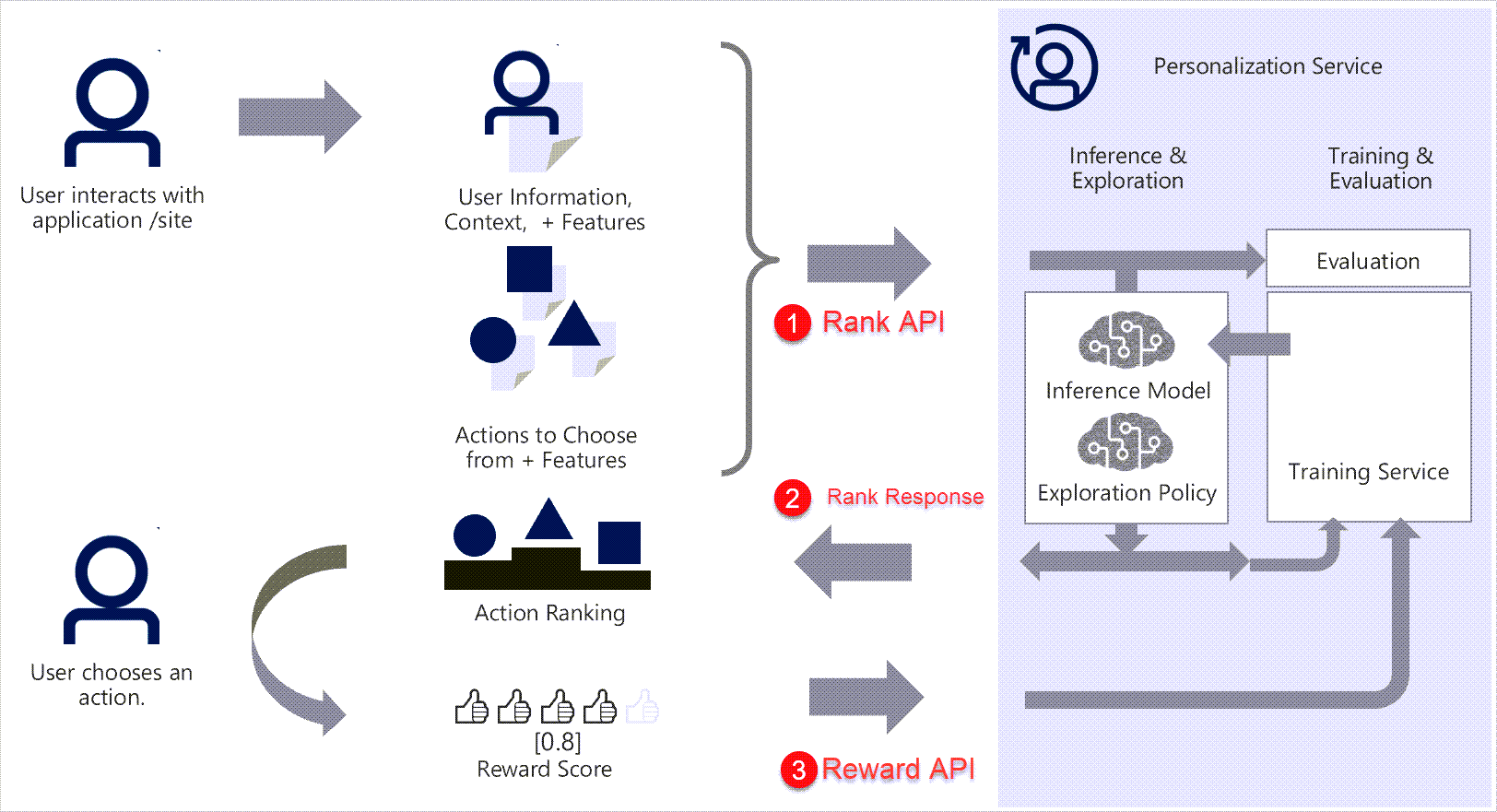

Azure Personalizer

Azure Personalizer System Design

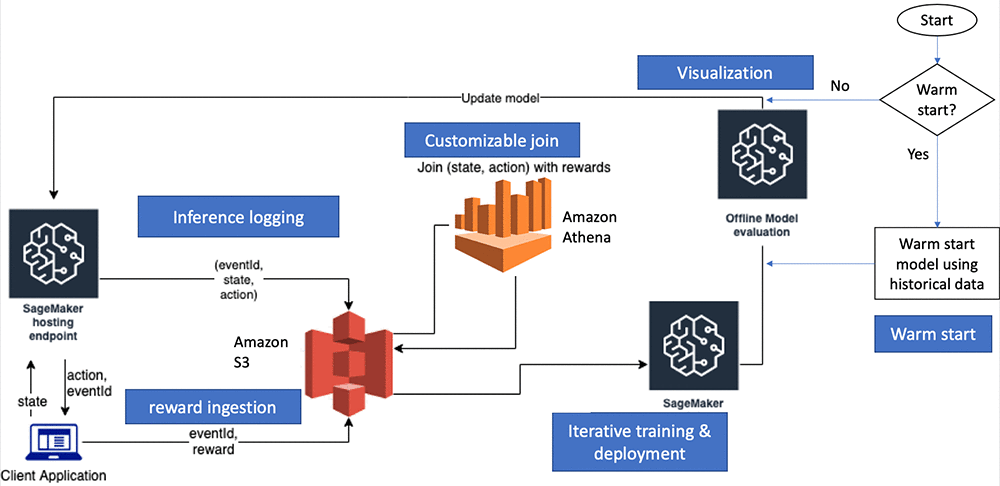

AWS SageMaker

RL system design in AWS SageMaker

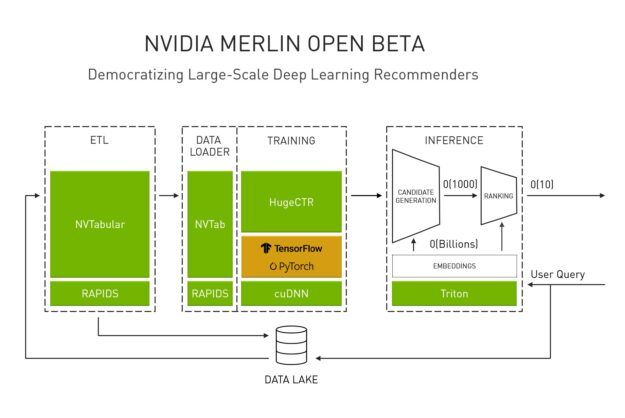

Nvidia Merlin

Nvidia Merlin

Google Recommendation

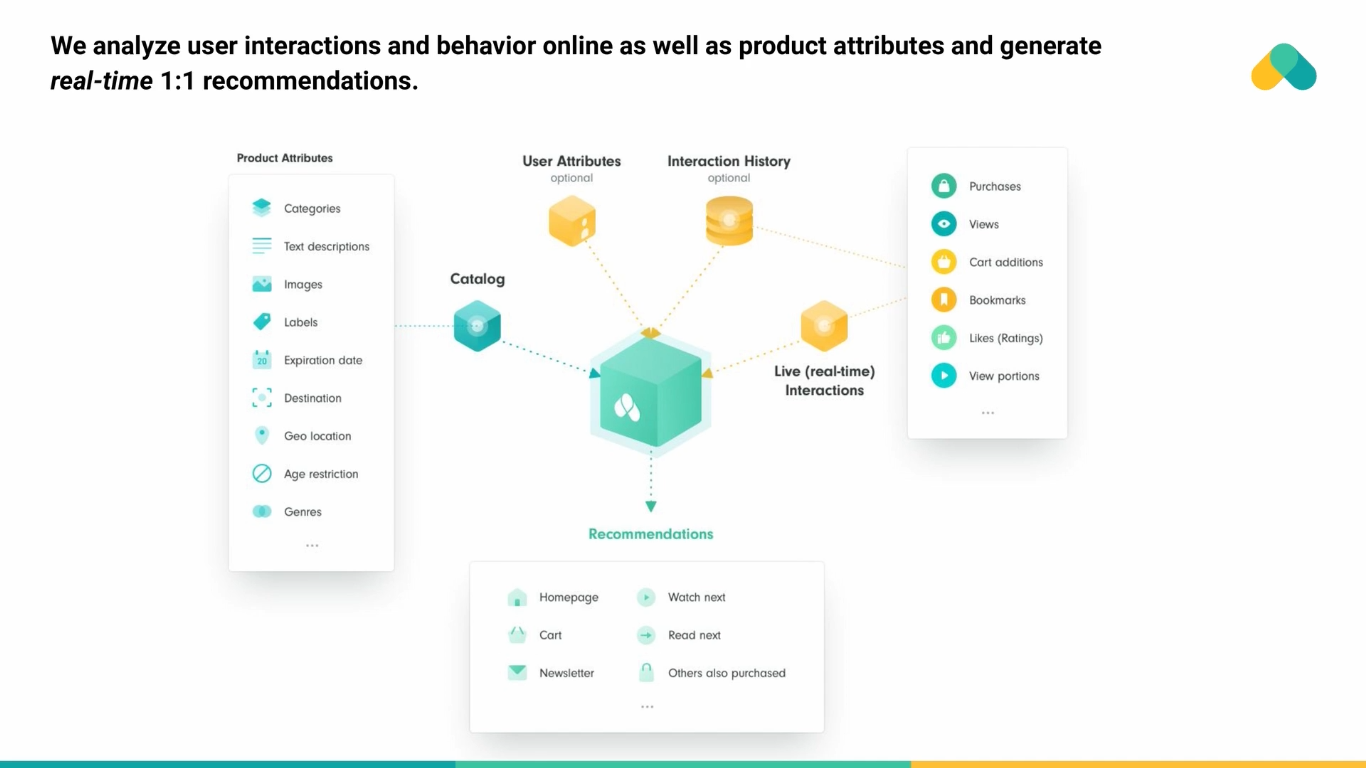

Recombee

Recombee

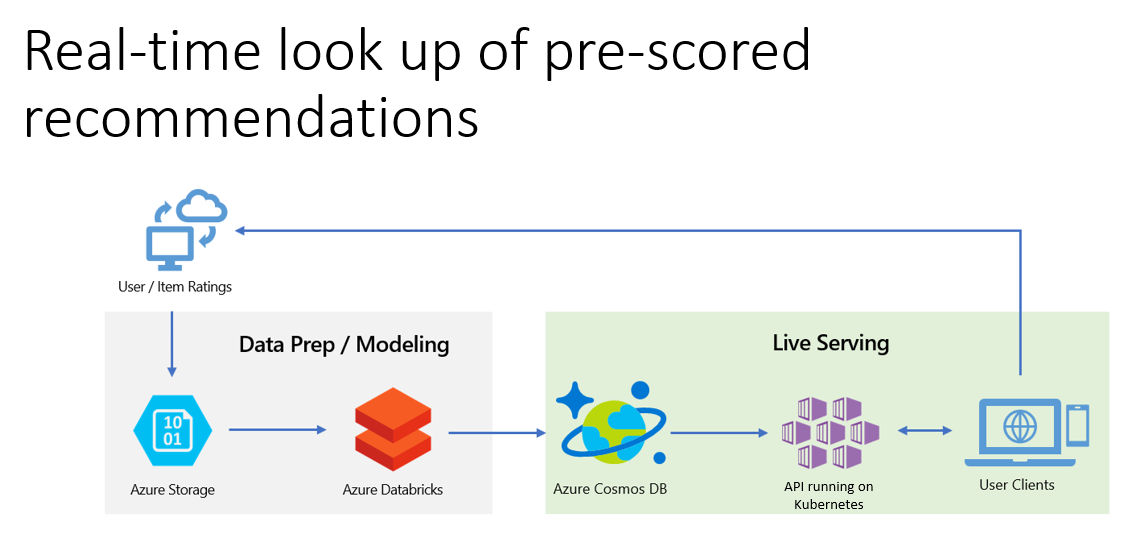

Azure Cloud

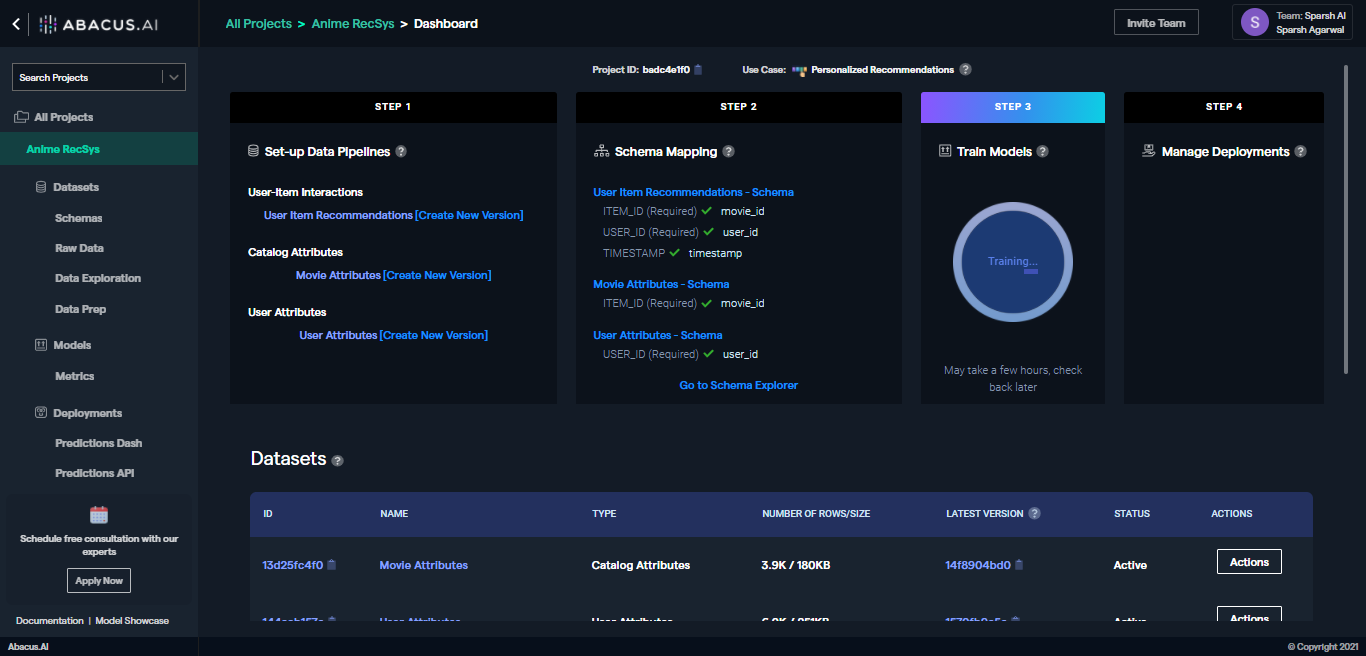

Abacus

Abacus AI

Classical Processes

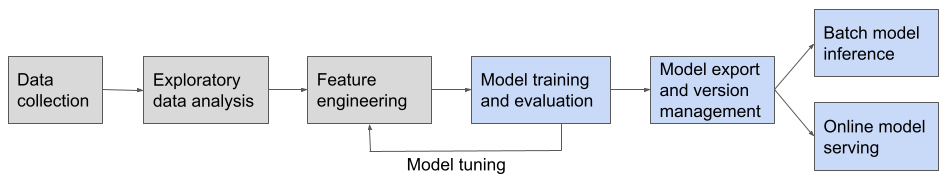

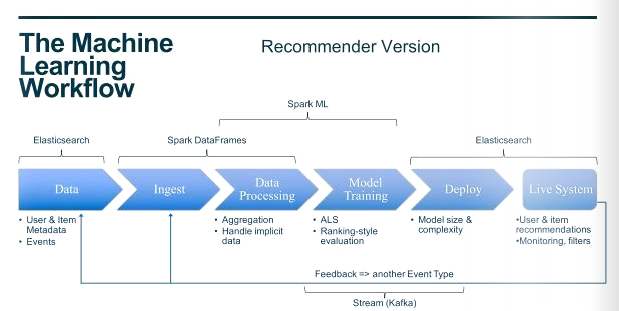

Machine Learning Processes

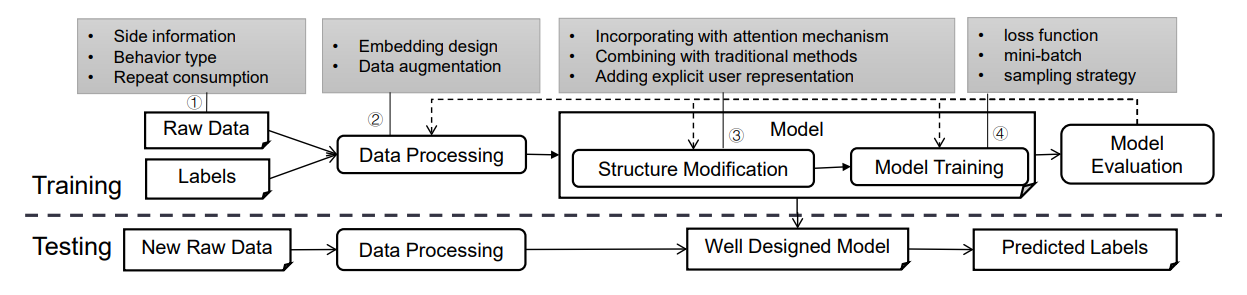

Influential factors of DL-based models.

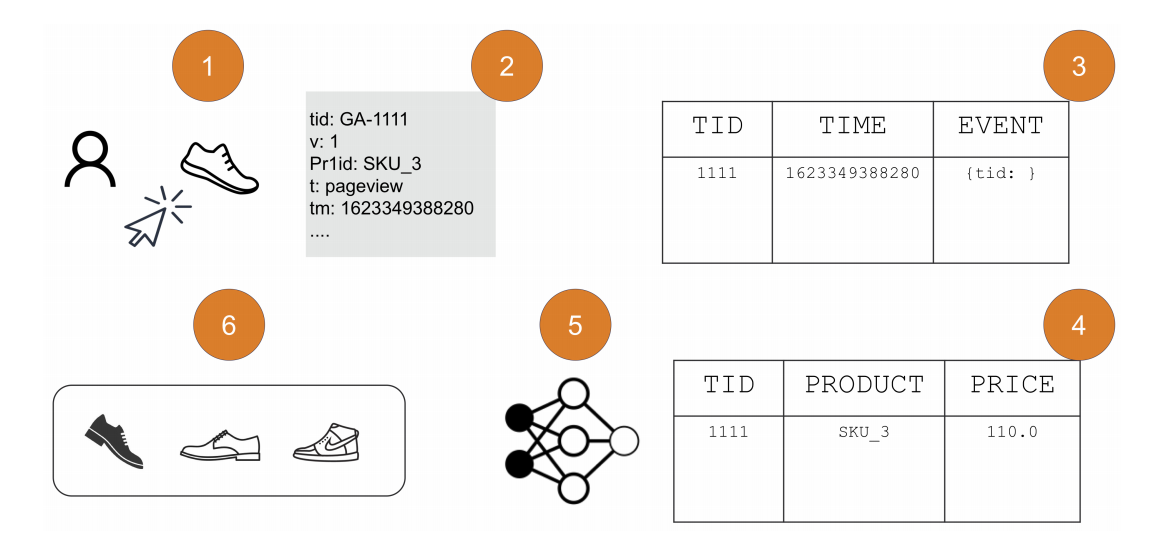

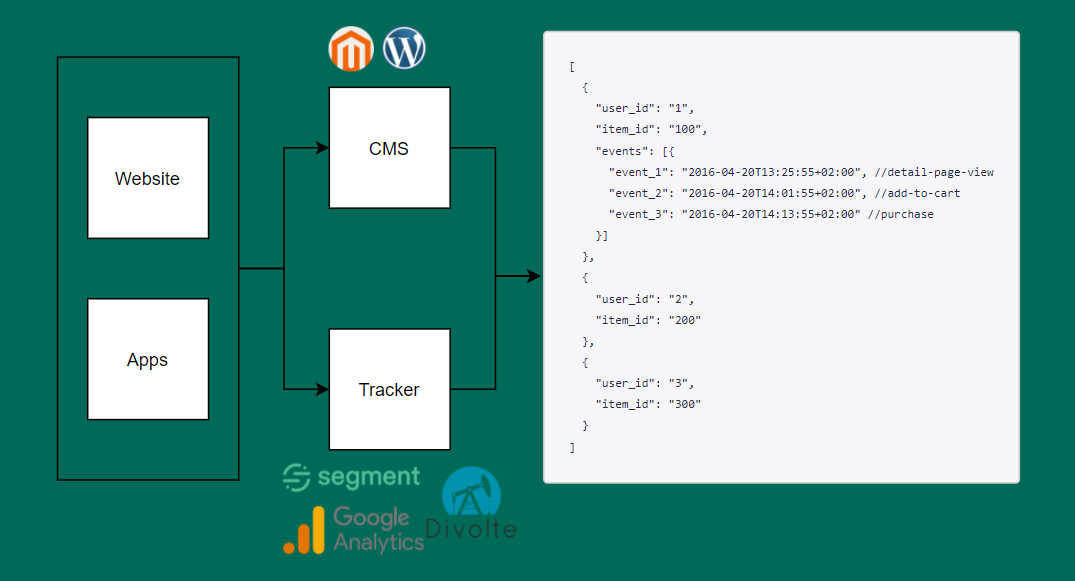

eCommerce Process

Data processing from events collected on the browser (shopper clicking on a product in 1), to a carousel of recommendations served on the PDP, 6. Raw data (2) is sent to a table (3), and stored raw in an append-only fashion. From there, data is transformed in usable format for training (for example, exploding important properties in a devoted table, 4), and a model is then trained (5) to serve recommendations (6). source.

CTR Process

Real-time Data Capturing Process

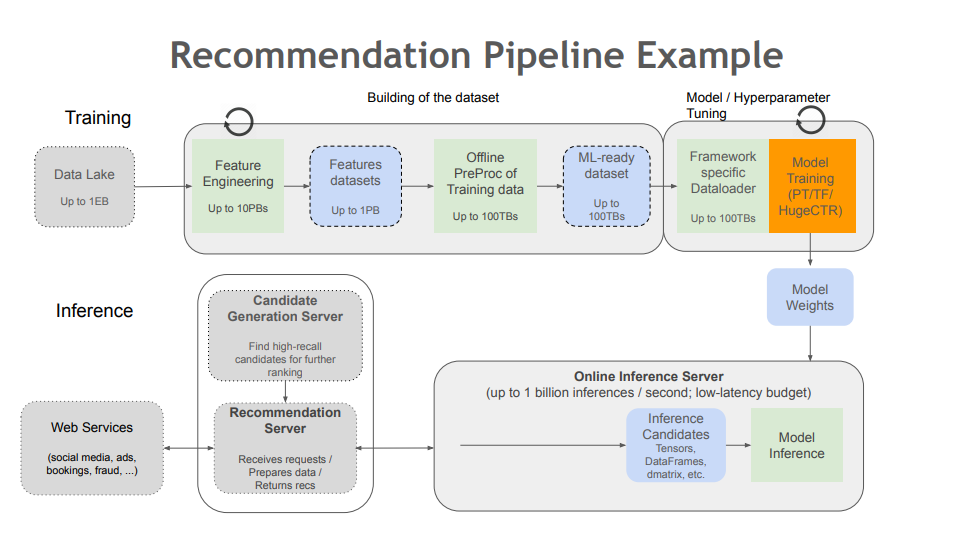

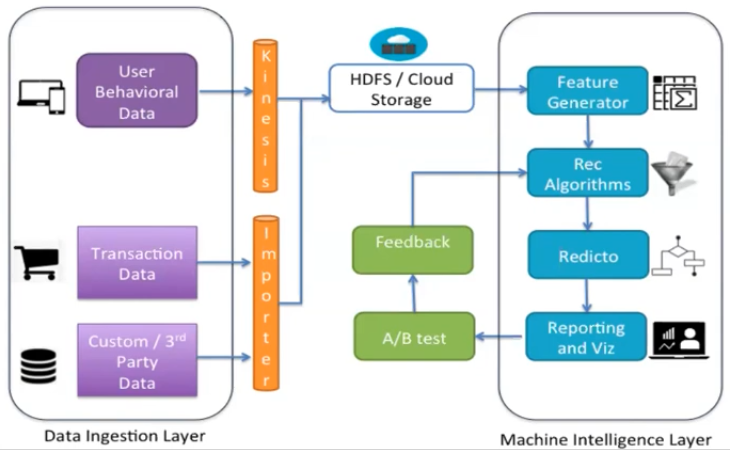

Large-scale Pipeline

Modern rec pipelines

Drivetrain Approach

Drivetrain approach

Standard Recommendation Modeling

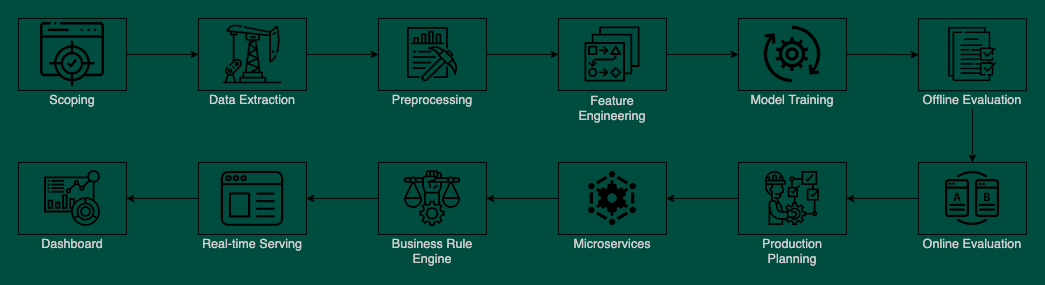

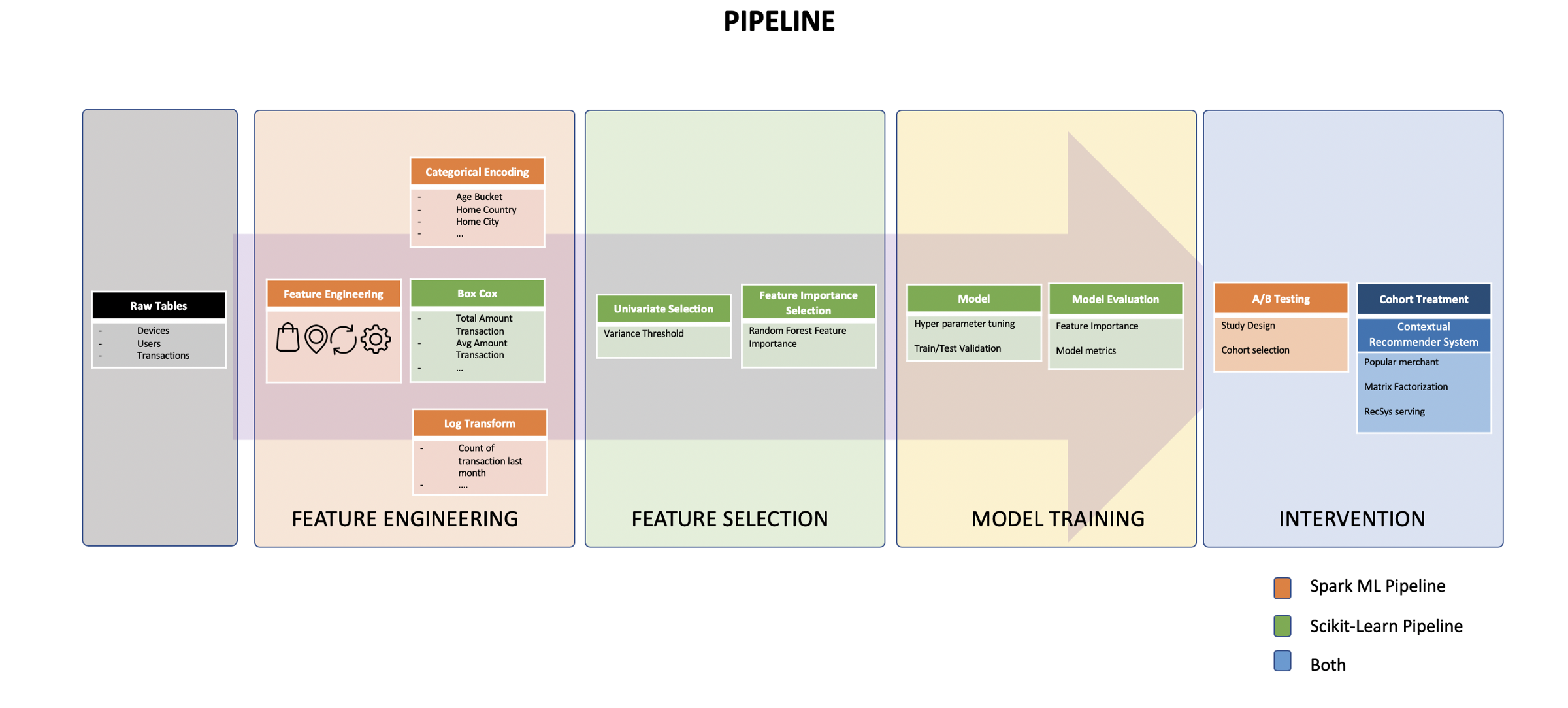

Standard Steps

Scoping > Data Extraction > [raw bucket] > Preprocessing > [refined bucket] > Feature Engineering > [consumption bucket] **> Model Training > Offline Evaluation > Online Evaluation Production Planning > Representation Service > Candidate Generation Service > Inference Service > Business Rule Service > Recommendation Service Dashboard > MLOps.

Standard Pipeline

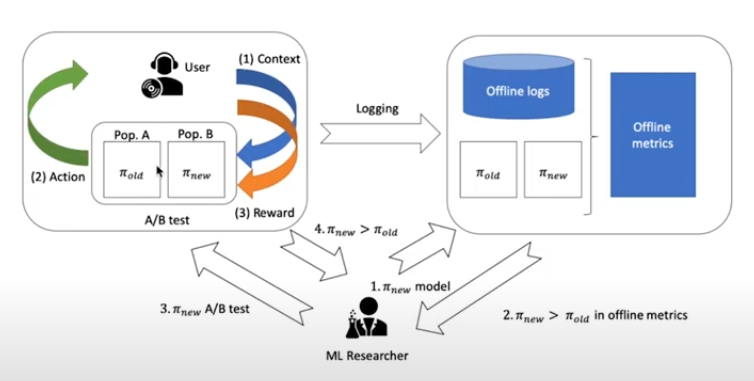

A/B Test Framework

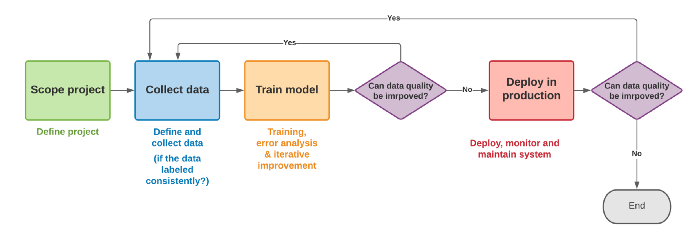

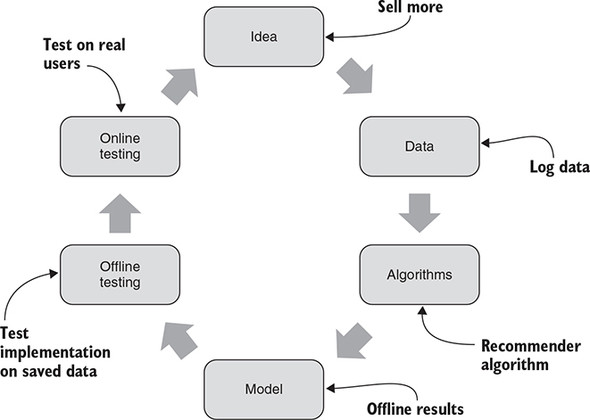

Standard Cycle

Business Project Process

Discovery and Analysis Phase

Before the project starts, it is essential to set up business and project objectives. The primary goal of this phase is to conduct a feasibility study.

The work on every project starts with the analysis. We analyze current metrics, data assets, and customer goals and processes. During that stage, the team defines the growth points, determines the technological stack, timeline and budget, and develops all corresponding documentation.

At the end of this phase, our business analysts find out whether we should use machine learning or the traditional algorithms to reach customer goals. Finally, we determine the scope of work needed for the prototype or MVP development.

After all the requirements are gathered, problems and goals are analyzed, the data is digitized, we proceed to the second stage. By the way, the first project phase we do absolutely for free.

We should also note that often our clients request the raw estimation, so we provide the data according to our expertise and completed projects for other clients. Often such estimates are slightly inaccurate because we cannot calculate the risks accurately, what makes the raw assessment more expensive.

Prototype Implementation Phase

During the second phase, we develop the simple prototype of the recommendation engine according to the data gathered during the previous step to prove the hypothesis and show its efficiency. That phase is critical to calculate the final costs of AI-powered recommender development.

As we already said, the prototype is a business model created to test overall system feasibility and to demonstrate the proof of concept. It can be a text or drawing-based mock-up, or a more complex code-based prototype, depending on the project complexity. Each prototype is shown and discussed with the client.

Prototyping is a technique which allows us to confirm requirements and design choices. Prototypes are usually fast and cheap to build and easy to mend.

Before real development begins, it is mandatory to calculate the risks. As the primary requirements are already discussed in the early stage, we can provide a more accurate estimation for the final solution, taking into consideration the risks, software implementation, algorithm tuning, and long or short-term maintenance.

We are striving to make this step as quick and inexpensive as possible. The prototype price may vary depending on many factors, but usually, it is under $5.000 for the recommendation engine.

Minimum Viable Product (MVP) Development

From the previous step, it may seem to you that the prototype is the alpha version of the recommendation system, but it is not.

The main difference between prototype and Minimum Viable Product: prototype proves the concept or idea – it is possible to extract insights from the data, and according to that insights generate suggestions and provide recommendations; MVP is an alpha version of a product, that solves the business goal – to increase the revenue or turnover.

MVP works with the client’s real data and is subjected to a group of real customers as the first version of the solution, collecting the relevant feedback. It is usually much cheaper to develop a Minimum Viable Product than a complex, robust solution.

We already mentioned in another our article, that one of the most common problems we face during the recommender development is unpredictable performance. We cannot guarantee that the solution we develop will improve the return on investment (ROI) about 256%, but we can make predictions when we already have data after a small period. MVP is perfectly suitable in this situation: it helps us to collect the first data to make accurate predictions.

Another moment is cost reduction and ROI increase. Usually, the company wants us to develop a recommendation engine software is a young company without strict traditional management, so they are still agile.

Sometimes, when we present the recommendation system MVP to the customer, we see it solving another business goal, not the goal described in the specification but the most valuable one. Agile software development approach helps us to determine new goals every sprint, so we can continue to improve the existing code that already helps the customer while developing another product to solve the original issue.

Usually, the MVP of recommendation engine projects costs vary from $5.000 to $15.000, according to the number of data to process, and factors the algorithm should take into consideration while generating the suggestions.

Recommender Release and Deployment

During the last phase, we do improve the prototype of the recommendation engine to match the clients’ needs and integrate it with the existing infrastructure.

The final release can be delayed or even postponed according to many different factors. Often our clients choose agile software development and prefer to launch the recommender prototype, improving it over time.

As we already mentioned, prototype deployment is the best idea if you want to prove the hypothesis, but not the best option if you’re going to use it as is for an extended period. Sometimes even good-working prototypes lack stability. We usually recommend thinking twice, before prototype deployment.

Usually, we deploy our solutions to the cloud due to the benefits it provides, but sometimes it happens that our engineers visit customers on-site to set everything up.

This project phase usually is not expensive, and costs under $5000. But the final recommendation engine deployment price may vary according to the previous steps and stages.

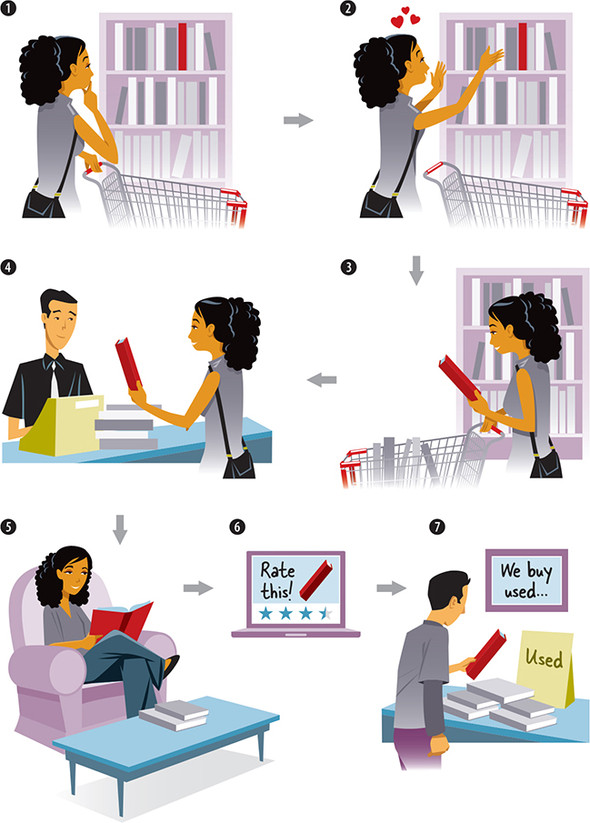

Customer Lifecycle

Consumer browses. As in a physical shop, the consumer looks around to see what’s there, with no specific goal. What’s noteworthy is where the consumer pauses and shows interest.

The consumer becomes interested in one or more products. It might be that the consumer knew from the start that they were looking for something specific or it might be by chance.

The consumer adds a product to the basket or a list with the intent to buy.

Consumer buys products.

Consumer consumes product. For example, the consumer watches the film or the consumer reads the book. If it’s a trip, the consumer goes on the trip.

Consumer rates the product. Sometimes consumers return to the shop/site to rate the product.

Consumer resells product or otherwise disposes of it. The consumer lifetime of the product is finished; it’s disposed of, deleted, or resold; in which case, the product probably goes through the same cycle again.

How to build a recommender system - Take 1

Outline a recommendation strategy

You can’t expect anything to go right if you approach it without a strategy. Ask yourself some questions:

- How often do you need to serve the recommended content? Real-time recommendations that take into account the most recent data are nice but more difficult to maintain. On the other hand, batch processing is easier to maintain (and in many cases perfectly sufficient) but does not reflect the recent changes in data.

- How will you handle the cold start problem? When a new customer starts using your platform, what will you recommend to them? The most common approach here is to serve them the most popular and the most recent content. That’s a good place to start learning what the user is interested in. However, you can also start with a clever onboarding process that will collect some basic information about what the user is interested in. That’s the case with Netflix, where the first step is to choose some movies and series that you’ve already seen and enjoyed. In the case of e-commerce businesses, you can simply recommend items similar to those they have already displayed.

- Do you want more feed diversity? Recommender systems filter the content and may sometimes filter it too strictly. If a user interacted with one type of content for some time – let’s say they watched 3 thrillers in a row, flooding their feed with thrillers is some idea, but is it a good idea? You can add some layer of randomization, suggesting other items as well to introduce more diversity.

- Do you want to explain the recommendations? Some suggestions are marked as “Because you watched X” or “Because you follow Y”, or they’re accompanied by the accuracy rate – on Netflix, next to each recommendation, there’s a certain percentage. It’s great to be able to show how your system came up with the recommendation, but it’s not that simple. Many machine learning models are black boxes: after they’re trained, they generate recommendations but without giving the rationale behind the decisions. The explanation is often not necessary, but if the recommendations are not accurate, users may question the model’s decisions. There are approaches addressing this issue, but the simplest solution is to state a few rules that are used in generating recommendations. These rules should be understandable to users but not too general like “based on historical data”. Tell your users how you do it, in simple steps, like: we collect the information about your activity and preferences and compare it to the activity of other users to find similarities; we then use this information to recommend items that users with similar preferences enjoyed. Make sure you are clear about whether you process any personal information.

Collect and organize relevant data

You cannot have a recommendation engine without data. Whatever type of a recommender system you choose, data is a must. As you collect information, make sure it is organized in some standard form. Having all information in the same form makes it easier to compare user A to other users, or item A to other items. The more relevant data you collect, the better predictions you get. That’s why some services have very specific sub-categories of products, like Netflix’s sub-genres.

Identify similarities

Between users, between products, or both. Compare the users or items to identify patterns. This can be done with the use of clustering algorithms, for example, the k-nearest neighbor (KNN) algorithm that recommends items that are closest to the ones users already liked. It’s the most intuitive machine learning algorithm – because it works similarly to how we give recommendations based on our knowledge of a person.

Track user interactions

The content you serve to users as recommendations is what you assume they will be interested in. With sufficient data, it’s very probable they actually will enjoy the suggested items, but you can’t just sit down and relax once the recommendation engine is in place. Track user interactions to assess user engagement and the quality of predictions. If you use systems including likes, upvotes, or ratings, your customers can provide you with feedback that helps further improve the recommendation engine.

How to build a recommender system - Take 2

Understand the business

Extremely simple and critical but often overlooked, the first step in building a recommendation system is defining the goals and parameters of the project. This will most definitely involve discussions between and input from both the data team as well as business teams (which might be product managers, operations teams, even partnership or advertising teams, depending on your product).

Here are some specific topics to consider to understand the business need more deeply and kickstart the discussion between these teams:

- What is the end goal of the project? Is the idea to build a recommendation system to directly increase sales / achieve a higher average basket size / reduce browsing time and make a purchase happen faster / reduce the long tail of unconsumed content / improve user engagement time with your product?

- Is a recommendation really necessary? This is perhaps an obvious question, but since they can be expensive to build and maintain, it’s worth asking. Can the business achieve its end goal by driving discovery via a static set of content instead (like staff/editor picks or most popular content)?

- At what point will recommendations occur? If recommendations make sense in multiple places (i.e., on a home screen upon first visiting the app or site as well as after purchasing or consuming content), will the same system be used in both places, or are the parameters and needs distinct for each?

- What data is available on which to base recommendations? At the time of recommendation, approximately what percentage of users are logged in (in which case there may be much more data available) vs. anonymous (which could complicate things for building the recommendation system)?

- Are there product changes that must be made first? If the team wants to build the recommendation system using more robust data, are there product changes that must be made first to identify users earlier (i.e., invite them to log in sooner), and if so, are they reasonable changes from a business perspective?

- Should all content or products be treated equally? That is, are there particular products or pieces of content that the business team wants to (or has to) promote aside from organic recommendations?

- How can users with similar tastes be segmented? In other words, if employing the model based on user similarity, how will you decide what makes users similar?

Get the data

The best recommendation systems use terabyte(s) of data. So when it comes to rounding up data to use for your recommendation systems, in general, the more the better. This can be difficult if users are unknown when you’re trying to make a recommendation for them — i.e., they’re not logged in or, even more challenging, they’re brand new. If you have a business where most users are unknown, you may need to rely on external data sources or general data not explicitly tied to preferences, like demographics, browsing history, etc.

When it comes to user preferences, there are two kinds of feedback: explicit and implicit.

- Explicit user feedback is anything that requires user effort, like leaving a review/rating or initiating a complaint or product return (often from customer relationship management, CRM, data).

- By contrast, implicit user feedback is information that can be gathered about a user’s preferences without them actually specifying those preferences. For example, past purchase history, time spent looking at certain offers, products, or content, data from social networks, etc.

Good recommendation systems usually employ a combination of these types of feedback since there are advantages and disadvantages to each.

- Explicit feedback can be very clear: a user has literally stated their preferences, likes, or dislikes. But by the same token, it’s inherently biased; a user doesn’t know what he doesn’t know (in other words, he might like something but has never tried it and therefore wouldn’t list it as a preference or interact with that type of item or content normally).

- By contrast, implicit feedback is the opposite — it can reveal preferences that a user didn’t — or wouldn’t — otherwise, admit to in a profile (or perhaps their profile information is stale). On the other hand, implicit feedback can be more complicated to interpret; just because a user spent time on a given item doesn’t mean that (s)he likes it, so it’s best to rely on a combination of implicit signals to determine preference.

Explore, clean and augment the data

One thing to consider when exploring and cleaning your data for a recommendation system, in particular, is changing user tastes. Depending on what you’re recommending, the older reviews, actions, etc., may not be the most relevant on which to base a recommendation. Consider only looking at features that are more likely to represent the user’s current tastes and removing older data that might no longer be relevant or adding a weight factor to give more importance to recent actions compared to older ones.

Datasets for recommendation systems can be challenging to work with because they are commonly high dimensional, but at the same time, it’s also common that many of the features don’t have any values, which can make clustering and outlier detection difficult.

Predict the ranking

Given the work done in the previous steps, you could have already built a recommendation system, simply by ranking those scores by users and you’ll have products to recommend. This strategy doesn’t use machine learning or a predictive element, but that’s totally fine. For some use cases, this is sufficient.

But if you do want to build something more complex, there are lots of subtasks that can be done after users consume recommended content that can be used to further refine the system. There are several ways to leverage the hybrid approach to try for the highest-quality recommendations:

- Presenting recommendations from different types of systems together side-by-side.

- Maintaining multiple algorithms in parallel where the decision of which algorithm is preferred over another is itself subject to machine learning (e.g., multi-armed bandit).

- Using a pure machine learning approach to combine multiple recommendation systems (logistic regression or other weighted regression methods). One specific example would be using a weighted average of two (or more) recommendations using different techniques.

It’s also possible that different models will work better in different parts of the product or website. For example, the homepage where the user has yet to take action vs. after the user has clicked or consumed content in some way.

Visualize the data

In the context of recommendation systems, visualization serves 2 primary purposes:

- When still in the exploration phases, visualizations can help reveal things about the data set or give feedback on model performance that would otherwise be difficult to see.

- After putting the recommendation system in place, visualizations can help convey useful information to the business or product teams (e.g., which content does well but isn’t being discovered, similarities between users’ tastes, content or products commonly consumed together, etc.) so they can make changes or decisions based on this information.

The primary issue with visualizing this type of data is the amount of data present, which can make it difficult to cut through the noise in a meaningful way. But by the same token, a good visualization will help make sense out of lots of data from which it would be otherwise difficult to derive meaningful insights.

Iterate and deploy models

Recommendation systems that are working in a development environment or sandbox don’t do any good. It’s all about putting the system into production so that you can begin to see the effect on the business goals you’ve laid out in the beginning.

Additionally, keep in mind that the more data you have with which to feed the recommendation system, the better it can become. So with this type of data project perhaps more so than others, it’s critical to evaluate performance and continue to fine-tune, like adding new data sources to see if they have a positive effect.

In fact, making sure your recommendation system is built to adapt and evolve by regularly monitoring its performance is one of the most important parts of the process — a recommendation system that isn’t properly adjusting to tastes or new data over time likely will not help you ultimately achieve your initial project goal, even if the system performed well at first. Building a feedback loop to understand whether or not users care about recommendations will be helpful and provide a good metric for making refinements and decisions going forward.

If recommendations are core to your business, constantly trying new things and evolving the initial model you’ve created will be an ongoing task; recommendation systems are not something you can create and cast aside.